Azahari Hassim

Is there a theological correlation between the Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad to Heaven and the prophecy mentioned in Daniel 7:13?

Please provide a detailed explanation to support this argument.

The argument connecting the Night Journey of the Prophet Muhammad to Heaven with Daniel 7 verse 13 is based on theological interpretations that draw parallels between the two events. Here’s an explanation of this argument:

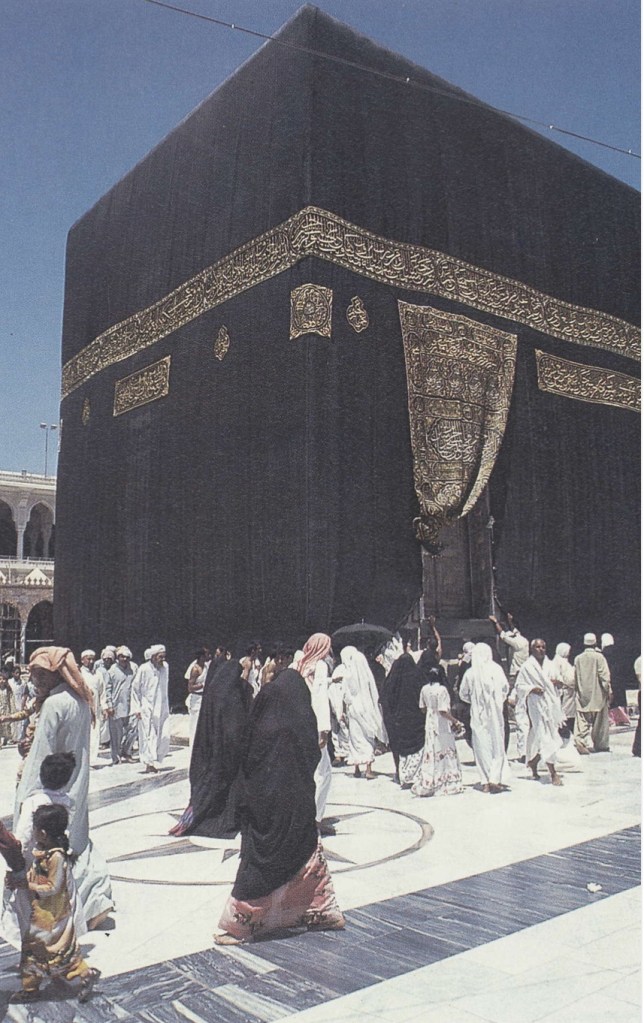

- The Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad ( الإسراء والمعراج): According to Islamic tradition, the Night Journey (الإسراء) and Ascension (المعراج) is a miraculous event in which the Prophet Muhammad was transported from Mecca to Jerusalem and then ascended through the heavens, meeting various prophets and eventually coming into the presence of Allah.

- Daniel 7 verse 13 in the Bible: In the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament of the Bible, specifically in Daniel 7 verse 13, there is a prophecy that says: “I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days (that is, God) and was presented before him.” This verse is often interpreted as a reference to a messianic figure.

The argument connecting these two events revolves around the idea that both the Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad and the vision in Daniel 7 verse 13 involve a figure coming into the presence of God. Some scholars, particularly in comparative religion and interfaith dialogue, suggest that there are thematic similarities between these events:

Divine Revelation: In both situations, there is a significant meeting with the divine, as Prophet Muhammad ascends to the highest levels of heaven, and the individual in Daniel 7 verse 13 is brought before the “Ancient of Days,” a divine being.

Prophetic Roles: The figure in Daniel 7 verse 13 is often associated with a messianic or prophetic role. Similarly, Prophet Muhammad is considered the final prophet in Islam, and his Night Journey is seen as a confirmation of his prophethood.

It’s important to note that this argument is primarily a matter of theological interpretation and interfaith dialogue. Different scholars and religious traditions may have varying perspectives on the significance and connections between these events.

Al-Suyuti (Islamic scholar and historian):“Daniel, peace be upon him, was among the prophets sent to the Children of Israel. He was blessed with wisdom and the ability to interpret dreams. He foretold the coming of several empires and their eventual downfall. His body was discovered during the conquest of Persia, and the Muslims respected it qand reburied it to protect it from being desecrated.”

What is the perspective of Islam on the biblical figure of Daniel?

In Islam, the perspective on the biblical figure of Daniel is quite respectful, though Daniel is not mentioned explicitly in the Quran. Despite this absence, Daniel is recognized and revered in Islamic tradition and literature, primarily through historical narratives and the Hadith (sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad).

Reverence in Islamic Tradition:

- Historical Narratives: Daniel is considered a prophet by some Muslim scholars, though this is not universally agreed upon since he is not mentioned in the Quran. His story and qualities are often cited in Islamic works, drawing from Jewish and Christian traditions. Islamic texts sometimes include stories about Daniel, portraying him as a wise and devout man. These narratives often focus on his ability to interpret dreams, his steadfast faith, and his survival in the den of lions—mirroring the biblical account.

- Literature and Folklore: Daniel appears in various Islamic texts and is particularly noted for his prophetic wisdom and piety. In some Islamic stories, he is credited with great wisdom and miraculous abilities, similar to those found in the Book of Daniel in the Bible. For instance, he is sometimes associated with the town of Susa in Iran, where a shrine said to be his tomb is located.

- Interpretations and Beliefs: In Islamic eschatology, Daniel is sometimes mentioned in discussions about the end times, although these references are more cultural and based on hadith literature rather than the Quran. His ability to interpret dreams and visions is often highlighted in Islamic teachings, paralleling the role he plays in the biblical narratives.

In summary, while Daniel is not a Quranic figure, his legacy as a wise and devout servant of God is acknowledged and respected within Islamic tradition, where he is often considered a prophet and a righteous man. His stories are used to impart moral lessons and to exemplify a life of faith and integrity.

How does Bart Ehrman interpret the term “son of man” as used by Jesus in the gospel?

Here is a summary of Bart Ehrman’s interpretation of Jesus’ use of the term “son of man” in the gospels:

1. Ehrman believes that when Jesus used the phrase “son of man”, he was referring to a future apocalyptic figure who would come as the cosmic judge at the end of time, not to himself. In other words, Jesus did not see himself as the “son of man”.

2. According to Ehrman, Jesus expected and taught that this “son of man”, a heavenly being sent by God, perhaps a powerful angel like Michael, would arrive imminently to judge the earth and establish God’s kingdom.

3. Ehrman argues this cosmic “son of man” figure derives from passages like Daniel 7:13-14, where he is portrayed as an exalted, divine-like figure subordinate only to God himself. However, Ehrman maintains this figure was still understood to be human, not divine, since that is what “son of man” means.

4. In Ehrman’s view, it was only after Jesus’ death that his disciples came to believe that Jesus himself was the “son of man” he had predicted would come. The gospels then place this title on Jesus’ own lips as a self-designation.

5. While Ehrman acknowledges that Paul seems to equate Jesus with the Danielic “son of man” in 1 Thessalonians, he argues these are likely later additions representing more developed Christology, not Jesus’ original teachings.

In summary, Ehrman’s controversial perspective is that Jesus did not use “son of man” as a title for himself, but rather to refer to a separate apocalyptic figure. This view contradicts the common interpretation that Jesus was claiming that title and identity directly. However, Ehrman’s arguments have generated significant scholarly debate and pushback from those who maintain Jesus did indeed see himself as the “son of man”.