Azahari Hassim

What distinguishes King Solomon from King Cyrus in relation to messiahship?

The main distinction between King Solomon and King Cyrus in relation to messiahship is:

- King Solomon was an Israelite king from the Davidic dynasty, while King Cyrus was a Persian king who ruled over the Israelites.

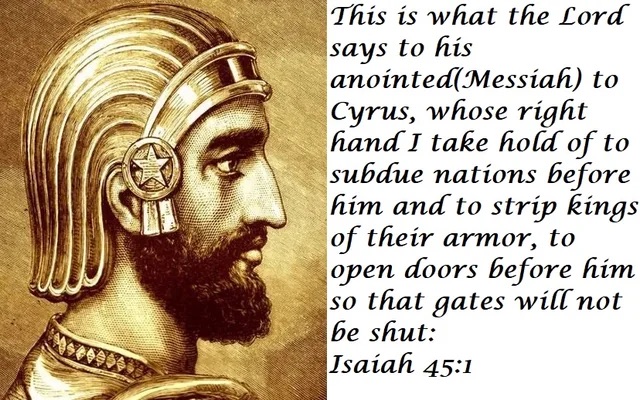

- King Solomon is not generally considered a messianic figure, though he was an important and influential king in the Old Testament. In contrast, King Cyrus is referred to as a “messiah” or “anointed one” in the Bible (Isaiah 45, verse 1).

- The reason Cyrus is referred to as a messiah is that, though he was not an Israelite, God used him to facilitate the return of the Jewish people from the Babylonian exile and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem. This was seen as a messianic act of delivering and restoring God’s people.

- Solomon, despite his wisdom and wealth, did not have the same messianic role or divine calling that Cyrus had in relation to the Israelites and their restoration. Solomon was an important king, but not considered a messianic figure in the same way.

So in summary, the key distinction is that Cyrus was explicitly called a messiah in Scripture for his role in facilitating the return from exile, while Solomon, though a great king, did not have the same messianic status or function in biblical theology.

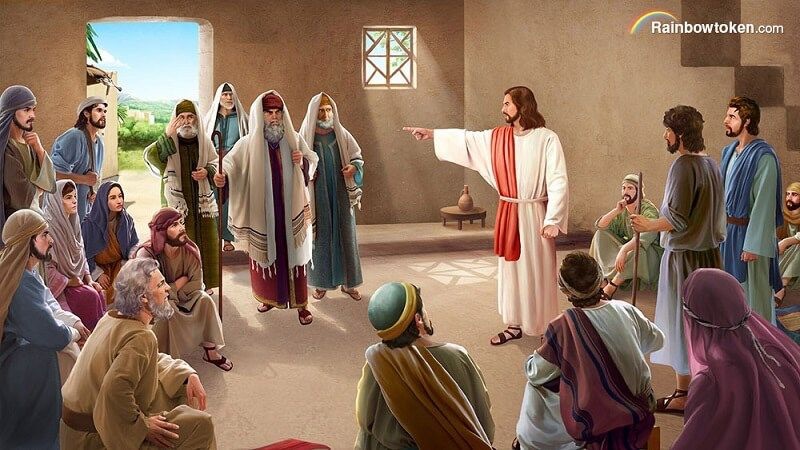

Jesus was teaching in the Temple area. He asked, “Why do the teachers of the law say that the Messiah is the son of David?

With the help of the Holy Spirit, David himself says, ‘The Lord (God) said to my Lord ( my master): Sit by me at my right side, and I will put your enemies under your control. ‘

David himself calls the Messiah ‘Lord.’ So how can the Messiah be David’s son?”

Many people listened to Jesus and were very pleased.

It has been argued by some Muslims that Jesus denies in Mark 12, verses 35 to 37, that the messiah Jews are looking for is a descendant of David. There is also a similar account in Luke 20, verses 41 to 44, and Matthew 22, verses 41 to 46. Their point of contention is that Jesus refers to Muhammad rather than himself. What is the significance of this argument?

The argument that Jesus refers to Muhammad in the above statements rather than to himself as the Messiah, and suggests that the Messiah Jews are awaiting is not a descendant of David, is an interpretation that emerges from a particular reading of these biblical passages in light of Islamic prophecy and eschatology.

This interpretation is not found within mainstream Christian theology but is part of Muslim perspectives that see Muhammad as the final prophet foretold in earlier scriptures, including the Bible. Here’s how this argument is typically explained:

- Jesus’ Questioning: Among Muslims, Jesus’ questioning is interpreted as a rejection of the idea that the Messiah is a physical descendant of David. Instead, they propose that Jesus is hinting at a more profound spiritual truth about the Messiah’s identity. This interpretation is seen as opening the door to the idea that Jesus might be indicating the coming of another prophet (Muhammad), as per Islamic belief, who is considered the final prophet and a messenger in Islam.

- Jewish Expectation: At the time, many Jews expected the Messiah to be a political or military leader who would liberate Israel from Roman rule. This expectation was based on various Old Testament prophecies that the Messiah would come from David’s lineage.

- Reference to Muhammad: Some Muslims interpret Jesus’ reference to “my Lord” as a prophecy about Muhammad, who is considered in Islam to be the final prophet and a “Spiritual Messiah.” This interpretation is bolstered by Islamic teachings that regard Muhammad as the “Praised One” (which is what the name Muhammad means) and as fulfilling biblical prophecies about a final messenger.

- Distinction from Davidic Lineage: By focusing on the term “Lord” and the context in which Jesus presents his argument, some Muslims see this as a clear indication that the coming Messiah, who they believe is Muhammad, would have a different role and authority than the one traditionally ascribed to the Davidic Messiah. This reading suggests that Jesus was pointing to the advent of a new spiritual leader who would come from the lineage of Ishmael, not Isaac, thus not being a direct descendant of David but still fulfilling the role of a Messiah.

- Islamic Eschatology and Prophecy: This interpretation is part of a broader Islamic eschatological view that sees Jesus and Muhammad as connected within God’s plan for humanity. Jesus is seen as heralding the coming of Muhammad, with his mission serving as a bridge between Jewish expectations of a Messiah and the arrival of the final prophet, Muhammad.

It’s important to note that this interpretation is specific to Islamic theology and is not shared by Jewish or Christian traditions, which have their own understandings of the Messiah and the prophecies concerning him.

Was Muhammad a promised Messiah to the Jews?

Allah says in the Quran, Surah 2 verse 89:

”And when there came to them (Jews) a Book from Allah, confirming that which is with them—and earlier they would pray for victory over the pagans (through the medium of His messenger)—so when there came to them what they recognized (that is, Muhammad), they denied it. So may the curse of Allah be on the faithless!“

Some believe this verse indirectly points to Muhammad as a promised Messiah. How is this interpretation explained?

This verse refers to the Jews who were awaiting the coming of their Messiah, as they had read about him in the scripture. They used to invoke Allah for his arrival, hoping that he would help them defeat their enemies. However, when Allah sent Muhammad to the Arabs, and he brought the Quran that confirmed the previous scriptures, the Jews rejected him and denied his prophethood. They did this out of envy and pride, because they wanted the Prophet to be from among them. Therefore, Allah cursed them for their disbelief and ingratitude.

The verse implies that the Jews had some knowledge of the characteristics and attributes of the Prophet Muhammad, and they recognized him when he came. This is also supported by other verses in the Quran, such as Surah 2, verse 146, which says:

”Those to whom We gave the Scripture know him as they know their own sons. But indeed, a party of them conceal the truth while they know [it].“

Therefore, some Muslims believe that this verse indirectly points to Muhammad as a promised Messiah, who was foretold by the previous prophets and scriptures.

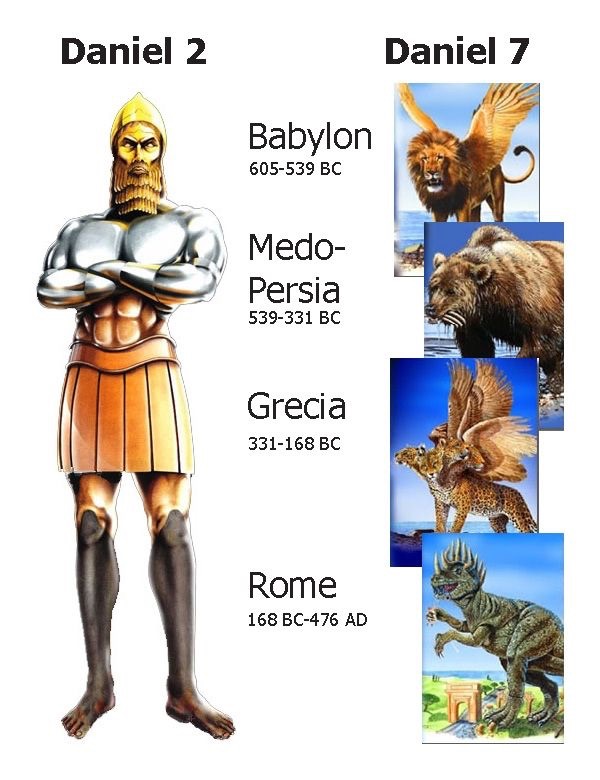

Certain individuals posit that Daniel 7, verse 25, can be interpreted as an allusion to Constantine the Great, the prominent figurehead of the Council of Nicaea, while they also propose that Daniel 7, verse 13, may be a reference to Muhammad’s celebrated Night Journey. How is this argument articulated?

This argument is highly controversial and not accepted by Christians. According to mainstream interpretation, Daniel 7, verse 25, refers to the Antichrist, while Daniel 7, verse 13, refers to the Messiah. However, some proponents of this argument offer the following explanation:

They argue that Constantine the Great, the Roman emperor who converted to Christianity and convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, is seen as the little horn mentioned in Daniel 7, verse 25. They claim that Constantine, through his actions, spoke against the Most High and attempted to change religious practices, such as introducing the doctrine of the Trinity, celebrating Easter instead of Passover, and observing Sunday rather than Saturday as the Sabbath. They also accuse Constantine of persecuting those who did not conform to his version of Christianity, particularly the Arians who denied the divinity of Jesus.

Regarding Muhammad, the founder of Islam, they argue that his Night Journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and subsequent ascension to heaven aligns with the Son of Man mentioned in Daniel 7, verse 13. They believe this refers to Muhammad being granted dominion, glory, and an everlasting kingdom by God. They assert that Muhammad restored monotheism and argue that his kingdom will never be destroyed, with all nations and peoples serving him or submitting to his law.