Azahari Hassim

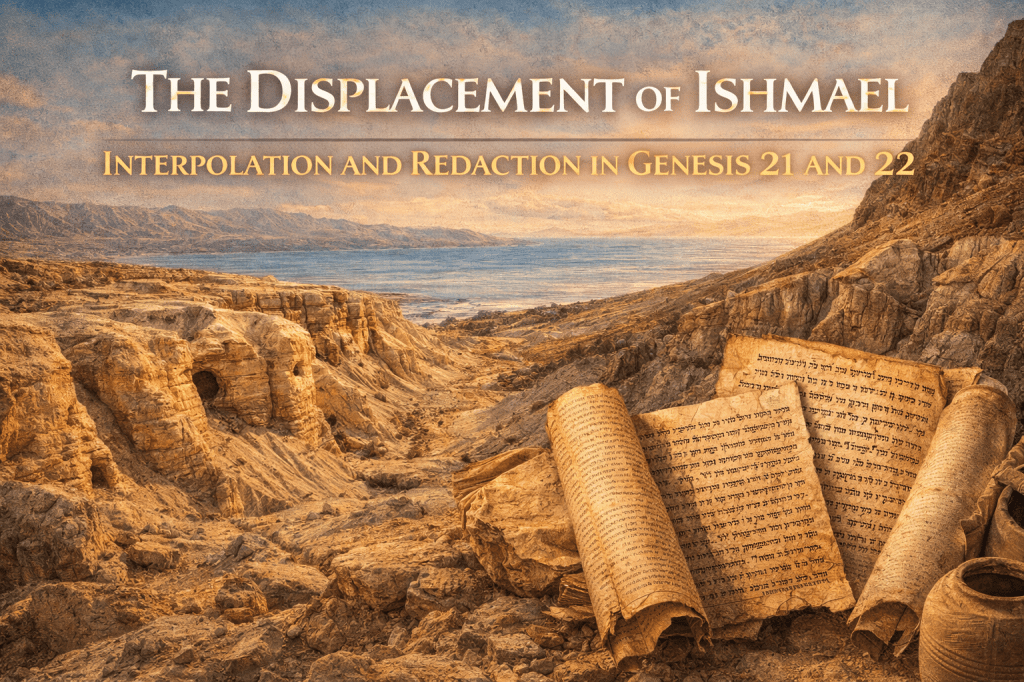

📜 The Displacement of Ishmael: Interpolation and Redaction in Genesis 21 and 22

📌 Abstract

Genesis 21:14–21 and Genesis 22 contain narrative features that suggest they originated in a tradition where Ishmael was Abraham’s only son, predating the covenantal promises of Genesis 17 and the birth of Isaac. A close literary-critical reading reveals that Genesis 21:9–10, which introduces Isaac into the episode, constitutes a later interpolation.

This insertion introduces Isaac into a story where Ishmael is still an infant, contradicting other textual references to his age and narrative function.

Similarly, the repeated naming of Isaac in Genesis 22 serves a redactional purpose: to elevate Isaac as the sole covenantal heir and obscure an earlier tradition in which Ishmael may have played that role. This article explores how these interpolations reshape ancestral memory, displacing Ishmael in favor of Israel’s later theological narrative.

⸻

🧩 1. Introduction: Recovering a Suppressed Narrative

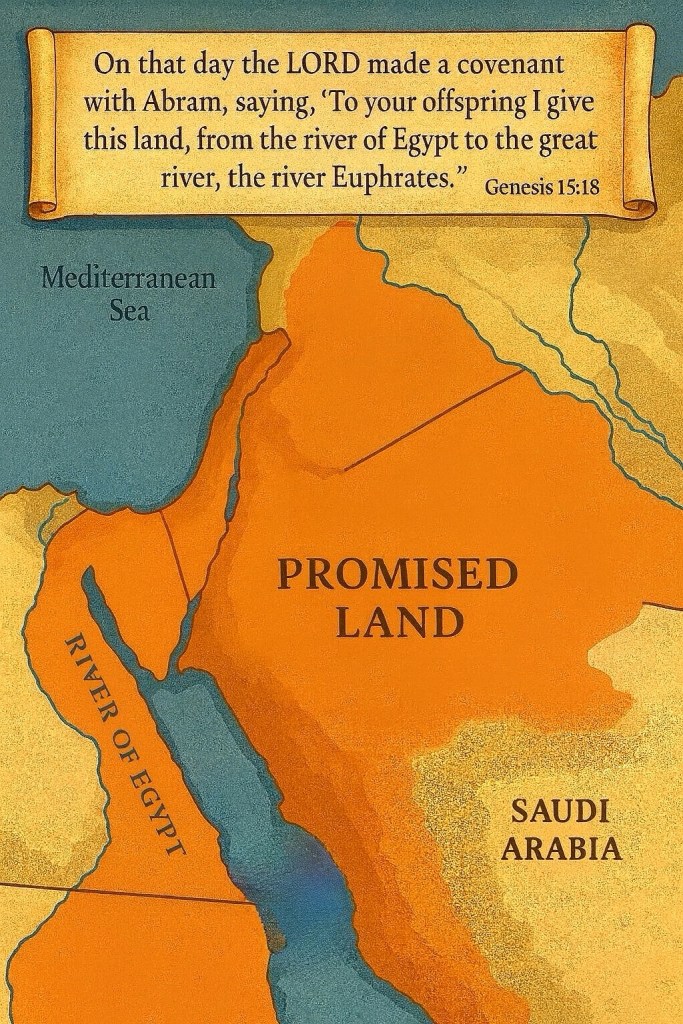

The Abrahamic cycle in Genesis includes two sons: Ishmael, the firstborn of Hagar, and Isaac, the promised son of Sarah. While Isaac is central to Israel’s covenantal lineage, several passages suggest that Ishmael once occupied a more central role—perhaps even as the intended heir. This study reexamines Genesis 21:14–21 (the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael) and Genesis 22 (the Akedah, or Binding of Isaac), arguing that these texts originally occurred before Isaac’s birth, and that Genesis 17, which introduces circumcision and confirms Isaac’s birth, functions as a later covenantal reconfiguration.

Central to this reinterpretation is Genesis 21:9–10, which appears to insert Isaac into a narrative where he logically should not yet exist. The surrounding context shows Ishmael as a helpless infant, not a teenage boy, further supporting the idea that this narrative reflects an earlier tradition prior to Genesis 17.

This displacement of Ishmael reveals an editorial strategy that rewrites Israel’s theological history to privilege Isaac as the son of the covenant, while subordinating or erasing Ishmael’s earlier significance.

⸻

👶 2. Genesis 21:14–21 – Ishmael as an Infant, Not a Teenager

The expulsion narrative in Genesis 21:14–21 depicts Hagar carrying the child and later placing him under a bush as he succumbs to thirst in the wilderness. The text repeatedly refers to “the child” (yeled) and “the boy” (na‘ar), emphasizing his vulnerability:

“When the water in the skin was gone, she put the child under one of the bushes. She went and sat down opposite him a good way off… for she said, ‘Let me not look on the death of the child.’” (Gen 21:15-16)

This imagery strongly suggests Ishmael is a very young child, likely an infant or toddler. However, if this narrative were to follow Genesis 17, Ishmael would be approximately 16 or 17 years old, having been circumcised at age 13 (Gen 17:25), and therefore too old to be carried or treated as a helpless baby.

This chronological contradiction indicates that Genesis 21:14–21 originally occurred before Genesis 17—in a time when Ishmael was the only son, and still very young. The language and setting reflect a pre-Isaac world. The editorial placement of this narrative after Isaac’s birth imposes a false sequence that undermines the original story’s integrity.

⸻

✂️ 3. Genesis 21:9–10 – A Theological Interpolation

In the midst of this narrative, Genesis 21:9–10 stands out:

“And Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had borne to Abraham, mocking.

Therefore she said to Abraham, ‘Cast out this slave woman with her son, for the son of this slave woman shall not inherit with my son Isaac.’”

These two verses function as a single ideological unit and introduce material that is sharply out of sync with the surrounding narrative. Together, they insert Isaac into a story that otherwise unfolds in a pre-Isaac context.

They introduce three major disruptions:

1️⃣ Isaac’s name is introduced for the first time, abruptly and polemically, even though Isaac has not yet been born in the implied chronology of the surrounding verses.

2️⃣ The use of inheritance language (“shall not inherit”) reveals the hand of a later redactor seeking to resolve a theological rivalry that did not yet exist in the original narrative context. Inheritance presupposes a covenantal hierarchy formalized only in Genesis 17.

3️⃣ The emotional and theological polarity—“the son of this slave woman” versus “my son Isaac”—signals an editorial voice, not an organic narrative development. The language is juridical and exclusionary, unlike the more tragic and empathetic tone of the wilderness scene that follows.

From a literary-critical perspective, Genesis 21:9–10 functions as an interpolation block, retroactively inserting Isaac into a narrative originally centered on Ishmael alone. The purpose is transparent: to delegitimize Ishmael preemptively and assert Isaac’s exclusive claim before the covenant is formally articulated in Genesis 17.

This interpolation reframes the expulsion from a human tragedy and divine rescue into a theologically sanctioned removal of a rival heir. In doing so, the redactor overlays the covenantal logic of Genesis 17 onto an earlier, independent Ishmael tradition.

⸻

🔥 4. Genesis 22 – The Binding of “Your Only Son”

Genesis 22 presents another critical site of interpolation. The divine command begins:

“Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac…” (Gen 22:2)

Here, the phrase “your only son” (yeḥidkha) is problematic. If Ishmael is alive—and he is, according to Genesis 21—then Isaac is not Abraham’s only son. The text appears to deny Ishmael’s existence, further supporting the idea that the narrative has been retrofitted.

It is likely that the original version of Genesis 22 did not name Isaac at all, and instead featured a generic command:

“Take your son, your only son, whom you love…”

Such phrasing could have originally referred to Ishmael, particularly if the story dates to a time before Isaac’s birth. The repeated use of Isaac’s name in verses 2, 6, 7, and 9 reflects a formulaic style and reads like a later addition intended to clarify the theological point: Isaac, not Ishmael, is the true heir and the proper object of sacrifice.

This redaction shifts the narrative focus and redefines Abraham’s faith—not as loyalty to his firstborn, but as obedience in offering the son of the promise, even at great cost. This framing gains coherence only after Genesis 17 introduces Isaac as the child of promise. In an earlier version of the narrative (prior to its final redaction), Ishmael may have been the ‘only son’—the firstborn, beloved, and legitimate heir in a proto-Israelite memory.

⸻

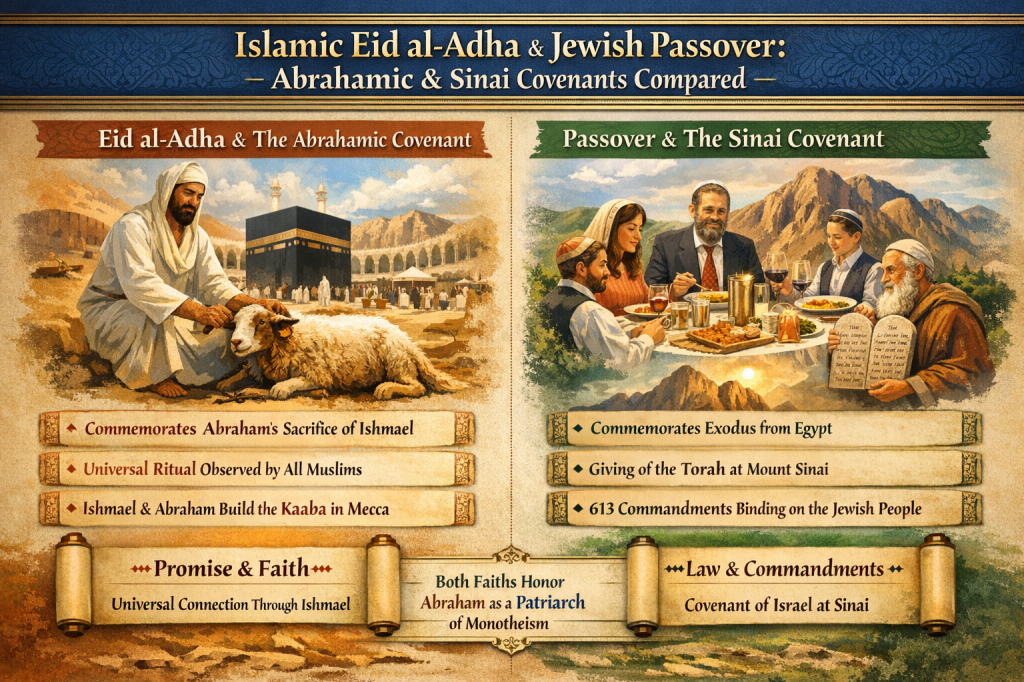

🔄 5. Genesis 17 – The Covenant That Rewrites the Past

Genesis 17 introduces circumcision and redefines the Abrahamic covenant around Isaac, even before his birth:

“Sarah your wife shall bear you a son indeed; you shall call his name Isaac: and I will establish my covenant with him…” (Gen 17:19)

This chapter is the turning point. It rewrites the narrative history, subordinating Ishmael (Gen 17:20) while preserving a blessing for him, and establishes Isaac as the theological heir. All subsequent texts are edited to conform to this covenantal framework.

Genesis 21:9–10 and the repeated naming of Isaac in Genesis 22 are part of this editorial theology. They serve to integrate older stories—likely composed in a context where Ishmael was the only son—into a new Israelite identity centered on Isaac and his descendants.

Redactional Note on Narrative Sequence

From a literary-critical perspective, the covenantal declaration of Genesis 17 is best understood as logically and theologically posterior to the sacrificial test of Genesis 22. In Genesis 22, Abraham undergoes a supreme trial of obedience and is rewarded with the divine proclamation that he will become the father of many nations (Gen 22:16–18). Only after this testing and confirmation does a covenantal redefinition of lineage make narrative sense. The placement of Genesis 17 before the sacrifice thus reflects editorial rearrangement, not original narrative chronology.

⸻

🕳️ 6. Conclusion: The Redactional Erasure of Ishmael

The textual evidence in Genesis 21:14–21 and Genesis 22 points to a displaced tradition—one in which Ishmael was the beloved and only son of Abraham, perhaps destined to inherit the promise before theological revision intervened. Through interpolation—most clearly in Genesis 21:9–10 and in the repeated naming of Isaac in Genesis 22—later editors sought to elevate Isaac and erase Ishmael’s prior status.

These interpolations are not mere insertions of names; they represent ideological transformations. The editorial hand reshaped ancestral memory to serve a covenantal theology that excluded Ishmael from inheritance—not merely of land, but of identity.

For the literary critic, these traces invite us to imagine what lies beneath the surface: a story of competing sons, competing claims, and a lost narrative in which Ishmael, even briefly, stood as Abraham’s only son.

⸻

📚 Selected Bibliography

• Friedman, Richard E. The Bible with Sources Revealed. HarperOne, 2003.

• Gunkel, Hermann. Genesis: Translated and Explained. Mercer, 1997.

• Van Seters, John. Abraham in History and Tradition. Yale, 1975.

• Kugel, James. How to Read the Bible. Free Press, 2007.

• Levin, Christoph. “The Yahwist and the Redaction of the Pentateuch.” JBL 124 (2005).

• Westermann, Claus. Genesis 12–36: A Commentary. Augsburg, 1985.

Who Wrote the Book of Genesis?

Tradition, Scholarship, and the Ongoing Debate

The question of authorship of Book of Genesis has long occupied both religious tradition and modern biblical scholarship. Unlike many ancient texts, Genesis does not identify its author within its own pages. Nor does any other book of the Bible explicitly name who wrote it. This absence has created a fertile ground for interpretation, debate, and evolving theories across centuries.

🕊️ The Traditional Attribution to Moses

Within Jewish and Christian tradition, Genesis has historically been attributed to Moses. This view did not arise arbitrarily. The remaining books of the Torah (or Pentateuch), such as Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, explicitly associate Moses with their composition, and biblical literature consistently treats the Torah as a unified body of sacred law and narrative. As a result, it was natural for ancient interpreters to regard Moses as the author of the entire collection, including Genesis.

There is also a compelling symbolic logic to this attribution. Moses, as the lawgiver and central prophetic figure of Israel’s formative period, seemed the most fitting individual to compile the book that narrates the origins of creation, humanity, and Israel itself. As has often been remarked, who better to write the book of beginnings?

🔍 The Limits of Tradition and the Rise of Critical Inquiry

Yet when tradition is set aside and the question is approached through historical and textual analysis, the evidence linking Moses directly to the writing of Genesis proves difficult to substantiate. The text of Genesis itself offers no explicit claim of Mosaic authorship, and internal features—such as shifts in style, vocabulary, and theological emphasis—have raised questions among scholars.

Over the past century, much academic scholarship has gravitated toward source criticism, a method that proposes Genesis is composed of multiple literary sources rather than a single author. These sources are often dated to the late pre-exilic and early post-exilic periods, long after the time traditionally associated with Moses. According to this view, Genesis reflects layers of tradition shaped and preserved over generations before being compiled into its present form.

🧠 Challenges to Source Criticism

Despite its influence, source criticism has not gone unchallenged. Advances in computer-assisted linguistic analysis have questioned whether the stylistic criteria used to separate sources are as reliable as once assumed. These studies suggest that variations in language may not necessarily indicate multiple authors, but could instead reflect genre, subject matter, or editorial purpose.

At the same time, alternative approaches such as redaction criticism have gained prominence. Rather than focusing primarily on identifying hypothetical sources, redaction criticism examines how the book was edited, arranged, and shaped into a coherent narrative. This perspective shifts attention from who wrote Genesis to how Genesis was formed and why it was structured in its final form.

📚 An Open Question Without a Final Answer

What emerges from this long history of debate is not a definitive conclusion, but a recognition of complexity. There is no shortage of theories regarding the authorship and composition of Genesis, and no single model has achieved universal acceptance. Tradition offers coherence and continuity; critical scholarship offers analytical depth and historical sensitivity. Each approach highlights different dimensions of this foundational text.

In the end, the authorship of Genesis remains an open and evolving question—one that continues to invite dialogue between faith, history, and literary study. Far from diminishing the book’s significance, this ongoing inquiry underscores its richness and enduring power as a text that has shaped religious thought for millennia.