Azahari Hassim

📜 Abraham, His Sons, and the House of God: A Comparative Study of the Bible and the Qur’an

🌟 Introduction

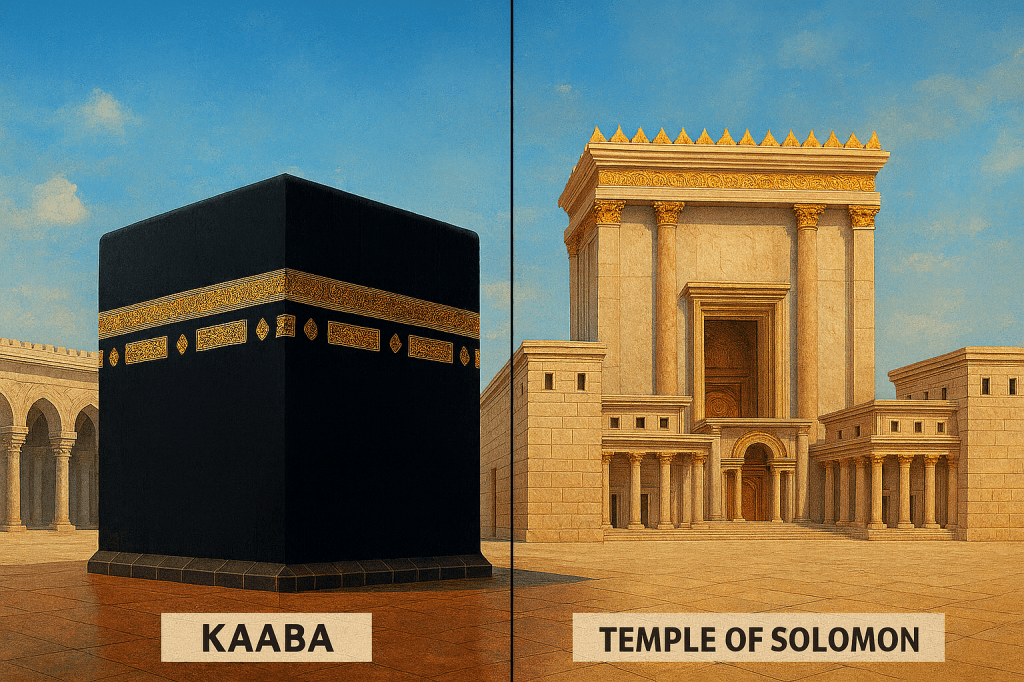

Across the Abrahamic traditions, the figure of Abraham stands as a foundational patriarch whose life, trials, and descendants shape the theological identity of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet the way these scriptures portray Abraham’s relationship to sacred places differs significantly. The Qur’an presents Abraham and his firstborn son Ishmael as the physical builders and consecrators of the Kaaba in Mecca. The Bible, in contrast, links Abraham and Isaac to the future Temple Mount through narrative association rather than construction. This distinction reveals how each tradition frames the origins of sacred space and the covenantal roles of Abraham’s sons.

⸻

♦️ 1. The Qur’an: Abraham, Ishmael, and the Kaaba

The Qur’anic narrative places Abraham (Ibrāhīm) and Ishmael (Ismāʿīl) at the centre of the establishment of the Kaaba, the primordial sanctuary in Mecca.

1.1 Building the Kaaba

The Qur’an explicitly describes Abraham and Ishmael raising the foundations of the Kaaba:

“And when Abraham raised the foundations of the House, and [with him] Ishmael, [saying], ‘Our Lord, accept this from us…’” (Qur’an 2:127)

This verse identifies them not only as worshippers but as architects of the House of God.

1.2 Dedication and Purification of the Sacred Space

Abraham and Ishmael are commanded to cleanse the House for those who perform worship, circumambulation, and devotion (Qur’an 2:125). Another passage speaks of Abraham leaving Ishmael’s descendants in the valley near the House to establish true worship (Qur’an 14:37), reinforcing their custodial role.

1.3 Universality of the Kaaba

The Qur’an describes the Kaaba as “the first House established for mankind” (Qur’an 3:96), giving it a universal, primordial character. Abraham and Ishmael thus appear not merely as historical figures but as founders of a sacred centre for all humanity.

In Islamic tradition, Abraham and Ishmael are understood as active constructors, purifiers, and guardians of the Kaaba — the earliest sanctuary dedicated to monotheistic worship.

⸻

♦️ 2. The Bible: Abraham, Isaac, and the Temple Mount

While the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh/Old Testament) also portrays Abraham as central to God’s covenantal plan, it does not attribute to him or to Isaac the establishment of a physical sanctuary.

2.1 Abraham and Isaac at Mount Moriah

Genesis 22 recounts the “Akedah,” or Binding of Isaac. God commands Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice “on one of the mountains in the land of Moriah” (Genesis 22:2).

Centuries later, 2 Chronicles 3:1 identifies this same region as the site of Solomon’s Temple:

“Then Solomon began to build the house of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord had appeared to David his father…”

This connection retroactively links the Akedah to the future Temple Mount. Yet the link is narrative and theological rather than architectural; Abraham and Isaac do not participate in constructing the sanctuary.

2.2 David and Solomon as Temple Builders

In the biblical tradition, the idea of a permanent sanctuary arises not with Abraham or Isaac but with King David. The Temple itself is built by Solomon (1 Kings 6), fulfilling David’s aspiration as narrated in 2 Samuel 7. Thus, temple-building is royal, not patriarchal.

⸻

♦️ 3. Key Difference: Builder vs. Symbol

A clear contrast emerges between the two scriptural traditions:

3.1 Qur’anic Perspective

• Abraham and Ishmael are direct builders and consecrators of the Kaaba.

• The sanctuary originates in their hands and through their supplication.

• The Kaaba becomes the focal point of monotheistic worship for all humanity.

3.2 Biblical Perspective

• Abraham and Isaac are linked to the site of the future Temple (Mount Moriah), but only symbolically.

• They do not build or establish a sanctuary.

• Temple-building is attributed to the Davidic-Solomonic monarchy.

3.3 Associative vs. Foundational

• The Bible connects Abraham and Isaac to the Temple through memory and location: the Akedah becomes part of Jerusalem’s sacred geography.

• The Qur’an connects Abraham and Ishmael to the Kaaba through construction and divine command: they physically establish the House of God.

⸻

♦️ Conclusion

Both the Bible and the Qur’an situate Abraham at the heart of sacred history, yet they portray his relationship to holy places in distinct ways. In the Qur’an, Abraham and Ishmael lay the physical and spiritual foundations of the Kaaba, making them architects of a universal sanctuary. In the Bible, Abraham and Isaac are remembered for their obedience at Moriah, a site later reinterpreted as the location of the Temple, but they do not build it.

These contrasting narratives shape how each tradition understands sacred space, lineage, and the enduring legacy of Abraham and his sons.

The Silence on Isaac: Semantic Tension and Narrative Discontinuity in the Hebrew Bible

🕊️ Introduction

The Akedah—traditionally known as the “Binding of Isaac” in Genesis 22—stands among the most pivotal and unsettling narratives in the Hebrew Bible. In this account, Abraham is commanded by God to offer his son Isaac as a burnt offering, a command that has shaped centuries of theological, ethical, and literary reflection. Yet beyond this single chapter, the Hebrew Bible is remarkably silent about Isaac as the intended sacrificial son.

This silence is not trivial. Given the gravity of the episode and its perceived centrality to Abrahamic faith, the absence of any further reference to Isaac’s near-sacrifice generates a profound semantic and theological tension within the canon. For many scholars, this tension raises questions about the narrative’s coherence, compositional history, and theological positioning.

⸻

🔥 Genesis 22 and the Unique Naming of Isaac

Genesis 22 opens with striking directness:

“Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac…” (Gen. 22:2)

The command unfolds in a layered identification: your son, your only son, whom you love, culminating—almost belatedly—in the name Isaac. The rhetorical progression heightens emotional intensity while simultaneously raising semantic difficulty. At the narrative level, Abraham already has another living son. At the canonical level, this is the only instance in the entire Hebrew Bible where God explicitly names Isaac as the subject of a sacrificial command.

This uniqueness is conspicuous. No other passage in the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, apart from Genesis 22, reiterates, interprets, or even recalls Isaac as the child placed upon the altar. The Akedah stands alone, self-contained, and curiously unreferenced.

⸻

📖 Canonical Silence Beyond Genesis 22

Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, Abraham is repeatedly celebrated as a model of faith and covenantal loyalty. Texts such as Nehemiah 9:7–8, Isaiah 41:8, and Psalm 105:9–10 recall God’s covenant with Abraham, yet none allude to the near-sacrifice of Isaac.

Equally striking is the portrayal of Isaac himself. He is never remembered as a near-martyr, never described as sanctified by suffering, and never associated with the climactic trial that supposedly defined his father’s faith. Instead, following Genesis 22, Isaac recedes into the background of the narrative, emerging as a largely passive patriarch.

If the Akedah were as foundational as later tradition assumes, its absence from Israel’s collective memory—as preserved in scripture—demands explanation.

⸻

🧩 Semantic Tension and Narrative Disruption

The isolation of Genesis 22 creates a deep semantic fracture. If Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac represents the apex of faith and obedience, why is this episode never integrated into the broader theological discourse of the Hebrew Bible? In other words, how can an event presented as the supreme test of Abraham’s faith remain canonically isolated, unreferenced, and theologically underdeveloped elsewhere in the Hebrew Scriptures?

Many scholars have noted that Genesis 22 reads as abrupt and self-contained, almost detached from its narrative surroundings. This has led to several interpretive proposals. Some suggest that the story functions as a theological parable rather than a historical memory. Others argue that it represents a late literary insertion, preserved but not fully assimilated into Israel’s evolving theological framework.

Still others propose that the silence is deliberate—a narrative strategy that forces readers to grapple with the disturbing implications of divine testing without offering interpretive closure.

⸻

👥 Reconsidering the Identity of the Intended Son

A more controversial line of inquiry questions whether Isaac was originally the son intended for sacrifice. Prior to Isaac’s birth, Ishmael was Abraham’s only son for nearly fourteen years. Within that earlier historical horizon, the phrase “your son, your only son” would have referred unambiguously to Ishmael.

This observation has led some scholars to suggest that Genesis 22 may preserve traces of an earlier tradition in which Ishmael occupied the central role. The ambiguity of the opening command—before Isaac’s name is specified—may reflect this older narrative stratum. According to this view, the later insertion or emphasis of Isaac’s name would align the story with a developing Israelite theology that privileged the Isaacic line of descent.

Support for this hypothesis is often drawn from the immediate literary context. Genesis 21 portrays Ishmael not as an adolescent, but as a dependent infant or very young child, carried by Hagar and laid beneath a shrub in the wilderness, with divine reassurance that he will yet become a great nation. Genesis 22, which follows immediately, again centers on the threatened loss of a son—but now one who is old enough to walk, speak, and participate in ritual action, as the child is led toward sacrifice rather than cast out in exile.

This deliberate narrative contrast—from infancy to maturity, from abandonment to offering—suggests a literary progression rather than a random juxtaposition. The proximity and thematic overlap of these chapters raise the possibility that they preserve parallel or developmentally staged traditions centered on the testing of Abraham through the loss of a beloved son, traditions that were later differentiated and theologically reoriented to privilege one lineage over another.

⸻

🤫 Isaac’s Silence and Narrative Aftermath

Perhaps most unsettling is Isaac’s own silence. After asking, “Where is the lamb for the burnt offering?” (Gen. 22:7), Isaac never speaks again in the episode. He offers no resistance, no lament, and no reflection. More striking still, the narrative records no meaningful interaction between Abraham and Isaac after the event.

Sarah’s death follows immediately in Genesis 23, and father and son are never depicted together again. This narrative void has prompted some scholars to suggest suppressed trauma or unresolved rupture—an interpretive shadow that lingers precisely because the text refuses to address it.

Later rabbinic traditions attempted to fill this silence, proposing that Isaac was permanently altered by the experience, or even that he briefly died and was resurrected. Such interpretations, however, underscore rather than resolve the absence within the biblical text itself.

⸻

⚖️ Scholarly Doubt and Theological Limits

The fact that Isaac’s intended sacrifice is never mentioned again in the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) has led modern scholars to question whether Genesis 22 was ever meant to function as a cornerstone of covenantal theology. Some interpret it instead as a polemic against child sacrifice, marking a transition toward animal substitution. Others see it as a theological experiment preserved precisely because it was too powerful—and too troubling—to repeat.

In either case, the narrative’s isolation suggests editorial hesitation. The moral stakes of the story may have been too severe to integrate comfortably into Israel’s broader depiction of a just and compassionate God.

⸻

🧠 Conclusion: A Story Remembered Once—and No More

Genesis 22 endures as one of the most scrutinized passages in the Hebrew Bible, not only for what it proclaims, but for what follows in its wake—namely, silence. The absence of any subsequent reference to Isaac as the intended sacrificial son introduces a lasting semantic tension into the biblical canon.

Whether this silence reflects literary strategy, theological discomfort, or the vestiges of an earlier tradition centered on Ishmael, it demands serious attention. The Binding of Isaac may be a story too sacred—or too unsettling—for repetition. Or it may stand as a palimpsest, preserving echoes of an earlier narrative in which Ishmael, not Isaac, stood at the center of Abraham’s supreme test.

In the Hebrew Bible, silence is never empty. Here, it speaks volumes. 🕯️