Azahari Hassim

🕋 The Abrahamic Covenant and the Sinai Covenant: An Islamic Perspective

Introduction

In the history of divine revelation, few themes are as central as the notion of covenant—a sacred bond between God and humankind. Both Judaism and Islam trace their spiritual origins to Abraham (Ibrāhīm عليه السلام), yet they diverge significantly in how they interpret the continuity and authority of that covenant. While Jewish tradition venerates the Ark of the Covenant (Aron ha-Berit) as the central relic of divine presence, Islam maintains a living connection to Abraham through enduring symbols such as the Kaaba (House of God), the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad), and the Station of Abraham (Maqām Ibrāhīm).

From an Islamic standpoint, this difference reflects not merely a matter of heritage, but a profound theological distinction between two divine covenants: the Abrahamic and the Sinai.

⸻

1. The Abrahamic Covenant and the Sinai Covenant

The Abrahamic Covenant represents God’s original and universal promise to Abraham—offering him descendants, land, and blessings for all nations (Genesis 12, 15, 17). It is viewed in Islam as the foundation of true monotheism and moral submission (islām).

In contrast, the Sinai Covenant (or Mosaic Covenant) was established later with the Israelites through Moses (Mūsā عليه السلام) at Mount Sinai. This covenant centered on the Law (Torah) and bound a particular nation to divine commandments. Islamic scholars interpret this as a temporary covenant intended to guide a specific community until the restoration of the universal Abrahamic faith.

⸻

2. Continuity and Fulfillment in Islam

Islamic theology asserts that Muslims are the true inheritors of the Abrahamic Covenant. This covenant, described as universal and eternal, transcends tribal or ethnic boundaries. It was renewed and fulfilled through Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, a direct descendant of Abraham through Ishmael (Ismāʿīl عليه السلام).

In contrast, the Sinai Covenant is seen as particular and conditional—its blessings dependent on Israel’s obedience to divine law. When that law was broken and the Ark of the Covenant lost, Islamic scholars view it as symbolizing the closure of that covenantal phase.

⸻

3. The Significance of Relics and Continuity of Faith

A striking contrast between Judaism and Islam lies in the preservation of relics tied to their covenantal heritage.

• Judaism possesses no surviving Abrahamic relic; the Ark of the Covenant—the holiest object of ancient Israel—was associated with Moses, not Abraham, and disappeared after the First Temple’s destruction.

• Islam, by contrast, maintains tangible Abrahamic relics: the Kaaba (House of God), built by Abraham and Ishmael; the Black Stone, believed to mark God’s covenantal witness; and the Station of Abraham, where he stood during construction of the Kaaba.

Islamic scholars often interpret this continuity of relics as an enduring testimony that Islam preserves the living Abrahamic legacy in both spirit and form.

⸻

4. The Ark of the Covenant and the End of the Sinai Order

The Ark of the Covenant served as the focal symbol of God’s presence in Israelite religion, containing the stone tablets of the Law revealed to Moses. However, its loss during the Babylonian destruction of the First Temple is understood in Islamic thought as emblematic—the withdrawal of divine favor from a covenant that had fulfilled its temporal purpose.

In contrast, Islam views the Kaaba as the restored House of God (Bayt Allāh), representing a continuous line of divine worship from Adam to Abraham and finally to Muhammad ﷺ.

The Ark belonged to the age of law, but the Kaaba belongs to the age of unity. The former was carried by priests; the latter is circled by all believers.

⸻

5. Lineage and Restoration of the Original Faith

Islamic scholarship emphasizes that Prophet Muhammad ﷺ descends from Abraham through Ishmael, preserving the original monotheistic lineage. This genealogical link reinforces Islam’s claim as the restoration, rather than innovation, of Abraham’s faith.

Thus, Islam positions itself not as a new religion but as the revival of the primordial covenant—the same faith of Abraham, purified from human distortions and reaffirmed for all nations.

⸻

6. Universality and Particularity

Theologically, Islam presents the Abrahamic Covenant as universal, extending to all humanity through submission to one God. By contrast, the Sinai Covenant is viewed as particular, restricted to the Israelites and their historical experience.

This distinction underscores Islam’s claim that the divine message, once localized in Israel, has now been universalized through the final revelation of the Qur’an—fulfilling God’s promise to make Abraham “a father of many nations” (Genesis 17:5).

⸻

7. Supersession and Fulfillment

Some Islamic interpretations express a form of supersessionism, not in the sense of replacement but of completion. The Qur’an acknowledges earlier covenants while affirming that final guidance was perfected in Islam:

“This day I have perfected your religion for you, completed My favor upon you, and chosen Islam as your way.”

(Qur’an 5:3)

Thus, the Abrahamic Covenant, renewed through Muhammad ﷺ, is seen as the culmination of God’s redemptive plan that began with Abraham and reached universality through Islam.

⸻

Conclusion

The Islamic distinction between the Abrahamic and Sinai covenants is not merely historical but profoundly theological. The loss of the Ark, the absence of Abrahamic relics in Judaism, and the survival of the Kaaba and the Station of Abraham in Islam are read as symbolic of a divine transition—from the particular to the universal, from the Mosaic to the Abrahamic, from the temporal to the eternal.

In the eyes of Islamic scholarship, the covenant lives on not in a lost ark of gold, but in the living hearts of those who submit to God in the faith of Abraham—the father of all who believe.

📜 Abraham, His Sons, and the House of God: A Comparative Study of the Bible and the Qur’an

🌟 Introduction

Across the Abrahamic traditions, the figure of Abraham stands as a foundational patriarch whose life, trials, and descendants shape the theological identity of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet the way these scriptures portray Abraham’s relationship to sacred places differs significantly. The Qur’an presents Abraham and his firstborn son Ishmael as the physical builders and consecrators of the Kaaba in Mecca. The Bible, in contrast, links Abraham and Isaac to the future Temple Mount through narrative association rather than construction. This distinction reveals how each tradition frames the origins of sacred space and the covenantal roles of Abraham’s sons.

⸻

♦️ 1. The Qur’an: Abraham, Ishmael, and the Kaaba

The Qur’anic narrative places Abraham (Ibrāhīm) and Ishmael (Ismāʿīl) at the centre of the establishment of the Kaaba, the primordial sanctuary in Mecca.

1.1 Building the Kaaba

The Qur’an explicitly describes Abraham and Ishmael raising the foundations of the Kaaba:

“And when Abraham raised the foundations of the House, and [with him] Ishmael, [saying], ‘Our Lord, accept this from us…’” (Qur’an 2:127)

This verse identifies them not only as worshippers but as architects of the House of God.

1.2 Dedication and Purification of the Sacred Space

Abraham and Ishmael are commanded to cleanse the House for those who perform worship, circumambulation, and devotion (Qur’an 2:125). Another passage speaks of Abraham leaving Ishmael’s descendants in the valley near the House to establish true worship (Qur’an 14:37), reinforcing their custodial role.

1.3 Universality of the Kaaba

The Qur’an describes the Kaaba as “the first House established for mankind” (Qur’an 3:96), giving it a universal, primordial character. Abraham and Ishmael thus appear not merely as historical figures but as founders of a sacred centre for all humanity.

In Islamic tradition, Abraham and Ishmael are understood as active constructors, purifiers, and guardians of the Kaaba — the earliest sanctuary dedicated to monotheistic worship.

⸻

♦️ 2. The Bible: Abraham, Isaac, and the Temple Mount

While the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh/Old Testament) also portrays Abraham as central to God’s covenantal plan, it does not attribute to him or to Isaac the establishment of a physical sanctuary.

2.1 Abraham and Isaac at Mount Moriah

Genesis 22 recounts the “Akedah,” or Binding of Isaac. God commands Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice “on one of the mountains in the land of Moriah” (Genesis 22:2).

Centuries later, 2 Chronicles 3:1 identifies this same region as the site of Solomon’s Temple:

“Then Solomon began to build the house of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord had appeared to David his father…”

This connection retroactively links the Akedah to the future Temple Mount. Yet the link is narrative and theological rather than architectural; Abraham and Isaac do not participate in constructing the sanctuary.

2.2 David and Solomon as Temple Builders

In the biblical tradition, the idea of a permanent sanctuary arises not with Abraham or Isaac but with King David. The Temple itself is built by Solomon (1 Kings 6), fulfilling David’s aspiration as narrated in 2 Samuel 7. Thus, temple-building is royal, not patriarchal.

⸻

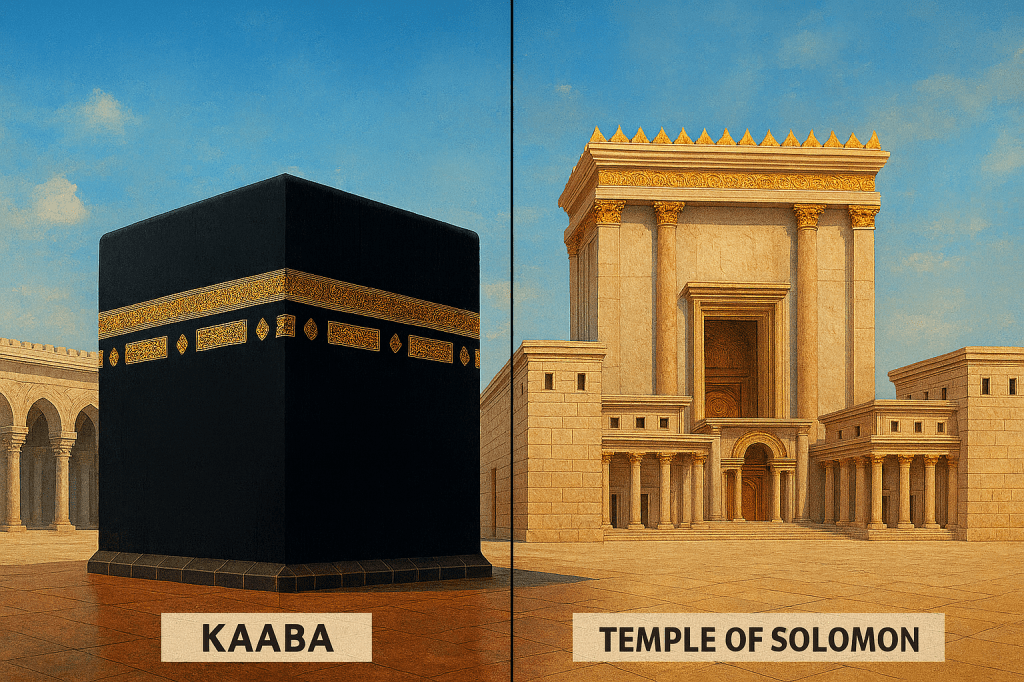

♦️ 3. Key Difference: Builder vs. Symbol

A clear contrast emerges between the two scriptural traditions:

3.1 Qur’anic Perspective

• Abraham and Ishmael are direct builders and consecrators of the Kaaba.

• The sanctuary originates in their hands and through their supplication.

• The Kaaba becomes the focal point of monotheistic worship for all humanity.

3.2 Biblical Perspective

• Abraham and Isaac are linked to the site of the future Temple (Mount Moriah), but only symbolically.

• They do not build or establish a sanctuary.

• Temple-building is attributed to the Davidic-Solomonic monarchy.

3.3 Associative vs. Foundational

• The Bible connects Abraham and Isaac to the Temple through memory and location: the Akedah becomes part of Jerusalem’s sacred geography.

• The Qur’an connects Abraham and Ishmael to the Kaaba through construction and divine command: they physically establish the House of God.

⸻

♦️ Conclusion

Both the Bible and the Qur’an situate Abraham at the heart of sacred history, yet they portray his relationship to holy places in distinct ways. In the Qur’an, Abraham and Ishmael lay the physical and spiritual foundations of the Kaaba, making them architects of a universal sanctuary. In the Bible, Abraham and Isaac are remembered for their obedience at Moriah, a site later reinterpreted as the location of the Temple, but they do not build it.

These contrasting narratives shape how each tradition understands sacred space, lineage, and the enduring legacy of Abraham and his sons.

Abraham Between Scriptures: Reconstructing the Ishmael Narrative

Introduction

📜 The Abraham narrative in Genesis remains one of the most theologically charged and textually complex portions of the Hebrew Bible. Traditionally, the canonical order—Genesis 17 (covenant and promise of Isaac), Genesis 21 (Ishmael’s expulsion), and Genesis 22 (the near-sacrifice)—forms the backbone of Jewish and Christian interpretations of Abraham’s faith.

📘 However, alternative readings, often emerging from comparative Islamic–Biblical studies and internal textual analysis, propose a different chronological sequence: Genesis 21 → Genesis 22 → Genesis 17.

📗 This reordered sequence offers a fresh interpretive lens that centers Ishmael in the formative stages of Abraham’s spiritual development. It also addresses several longstanding textual tensions—particularly the age contradiction in Genesis 21 and the reference to the “only son” in Genesis 22—while creating an integrative bridge between Biblical and Qur’anic portrayals of Abraham.

⸻

- Genesis 21:14–20 — The First Test: Ishmael’s Separation

🌿 In the canonical reading, Genesis 21 recounts the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael after Isaac’s birth. Ishmael should be approximately 16–17 years old at this point (Gen 16:16; 21:5). However, the narrative describes him as if he were a helpless infant carried by Hagar, unable even to stand or walk (Gen 21:14–20). This tension is one of the most noted inconsistencies in the Abraham narrative.

🌤️ In non-canonical interpretations, this episode is repositioned earlier in Abraham’s life—before Genesis 17, when Ishmael would indeed still be a small child. This re-sequencing not only resolves the age contradiction but also aligns closely with the Islamic tradition, where Ishmael is still an infant during the desert episode (associated with the origins of Mecca).

🌾 Viewed this way, Genesis 21 becomes Abraham’s first great test: releasing Ishmael into the wilderness in trust that God will preserve him and fulfill the promise, “I will make him a great nation” (Gen 21:18). This trial tests Abraham’s emotional endurance and his willingness to surrender Ishmael into divine care.

⸻

- Genesis 22 — The Second and Climactic Test: The Near-Sacrifice

🔥 Genesis 22, the story of the near-sacrifice, is considered the apex of Abraham’s trials in Jewish and Christian traditions. Yet the description of the son as ‘your only son’ presents a theological challenge if Isaac has an older brother. Ishmael, alive and older, remains Abraham’s son; thus Isaac cannot be described as the “only son” in any literal or historical sense.

🕊️ By placing Genesis 22 before Genesis 17, this difficulty vanishes: Isaac has not yet been promised; Ishmael is truly Abraham’s only son; and the command makes perfect narrative and emotional sense.

🗡️ In this alternative chronology, the near-sacrifice becomes the second and supreme test concerning Ishmael. Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his only heir and the bearer of the divine promise forms the climactic demonstration of his faith.

🌙 This view also naturally resonates with Islamic tradition, where the sacrificial son is widely understood to be Ishmael, not Isaac.

⸻

- Genesis 17 — Covenant Ratification After the Trials

🌟 In the canonical sequence, Genesis 17 precedes the trials of Genesis 21 and 22. But in the reordered interpretation, Genesis 17 becomes the divine ratification of Abraham’s faith after he has passed the two Ishmael-centered tests.

📜 In this reading, the promise of numerous descendants, the covenant of circumcision, the changing of Abraham’s name, and the announcement of Isaac’s future birth all occur after Abraham’s faith has already been tested and proven through his obedience concerning Ishmael.

👑 Genesis 17 thus becomes the culminating divine affirmation that Abraham is now fit to be “the father of many nations” (Gen 17:4–5).

⸻

- A Coherent Theological and Narrative Progression

🔎 The sequence Genesis 21 → Genesis 22 → Genesis 17 creates a remarkably coherent theological and literary framework.

📖 First, it resolves textual contradictions, such as Ishmael’s apparent infancy in Genesis 21 and the use of “your only son” in Genesis 22.

🕊️ Second, it highlights Ishmael’s covenantal significance by placing him at the center of Abraham’s formative spiritual testing rather than as a marginal figure displaced by Isaac.

🤲 Third, it aligns with the Qur’anic portrayal, which emphasizes Ishmael’s foundational role in Abraham’s obedience, making this sequence a natural bridge between the two traditions.

🌄 Fourth, it creates a natural developmental arc in which Abraham’s spiritual journey unfolds as Test 1: Surrender Ishmael (Genesis 21), Test 2: Sacrifice Ishmael (Genesis 22), and finally Covenant: God ratifies Abraham’s faith (Genesis 17).

🌱 Abraham’s journey becomes one of emotional surrender leading to ultimate obedience, culminating in divine covenant.

⸻

Conclusion

🌐 Although this reconstruction diverges from the canonical Jewish and Christian chronology, it offers a compelling alternative grounded in textual observations, theological coherence, and comparative Abrahamic studies.

🌙 It gives Ishmael a restored centrality in Abraham’s early faith narrative and provides an interpretive bridge between Biblical and Islamic traditions.

📚 By situating Genesis 21 and 22 prior to Genesis 17, this reading presents a unified, coherent, and theologically rich portrait of Abraham—one in which Ishmael’s role is not marginal but foundational to the covenantal story.