Azahari Hassim

✦ The Qur’an’s Silence vs. the Torah’s Voice

The Qur’an does retell the Abrahamic narrative but leaves certain elements unspoken: Hagar’s name, the name of the son to be sacrificed, circumcision, and even Zamzam.

⸻

✦ Introduction

The Qur’an recounts the story of Abraham (Ibrāhīm عليه السلام) with remarkable depth — his search for God, his trials, and his covenant. Yet on some of the most debated aspects of his legacy, the Qur’an remains silent: it does not name Hagar, the mother of Ishmael; it does not identify the son who was nearly sacrificed; it does not legislate circumcision; and it does not name Zamzam, the well that saved Ishmael’s line in the barren valley of Makkah.

To some, this silence seems puzzling. But when read against the backdrop of Jewish and Christian claims of covenantal exclusivity, the silence of the Qur’an is not absence — it is strategy. It universalizes Abraham’s covenant, bypasses rabbinic control of scripture, and positions Muhammad ﷺ and his Ummah (nation) as the true fulfillment of Abraham’s prayer.

⸻

✦ Hagar and Zamzam: The Forgotten Mother Remembered by Rites

• Torah: Hagar is remembered as the Egyptian servant, driven away. Her suffering becomes marginal to the covenant story, which centers Isaac.

• Qur’an: Hagar’s name is absent, but her story is enshrined in ritual. The sa‘y (ritual walking) between Ṣafā and Marwah (Q 2:158) immortalizes her desperate search for water. Zamzam is not named in the Qur’an, but every pilgrim drinks from it.

Theological Point: By omitting her name yet embedding her sacrifice into the Hajj, the Qur’an elevates Hagar from marginal slave to the mother of covenantal continuity — without needing textual polemics against the Torah.

⸻

✦ The Sacrificed Son: A Test Beyond Lineage

• Torah: Genesis 22 names Isaac as the intended sacrifice, tying the covenant firmly to Israel’s patriarch.

• Qur’an: The son is never named (Q 37:99–113). Early Muslim memory, however, identifies him as Ishmael.

Theological Point: Silence denies Jewish exclusivism the chance to argue “lineage proof.” Instead, the focus is shifted: covenant is about submission, not biology. In Islam, the moral weight of the sacrifice lives on in Eid al-Adha — commemorated globally — whereas the Torah prescribes no festival for the Akedah (The Binding of Isaac).

⸻

✦ Circumcision: From Physical Mark to Spiritual Covenant

• Torah: Circumcision is the everlasting “sign” of Abraham’s covenant (Genesis 17).

• Qur’an: No mention of circumcision at all. Instead, believers are called to follow “the millah of Abraham” (Q 16:123; Q 22:78).

Theological Point: By omitting circumcision, the Qur’an redirects the covenant away from bodily marks to spiritual submission. Abraham’s legacy becomes a matter of faith and obedience, not merely a cut in the flesh. Circumcision survives in Sunnah (the practice of the Prophet Muhammad), but the Qur’an shifts the axis of covenant from tribal identity to universal submission.

⸻

✦ The Jewish Perplexity and Envy

The rabbis of late antiquity held covenant as Israel’s exclusive treasure: Isaac, not Ishmael; Jacob, not Esau. But the Qur’an reframes it:

• “My covenant does not include the wrongdoers.” (Q 2:124)

• “Abraham was neither a Jew nor a Christian, but a ḥanīf, a Muslim.” (Q 3:67)

• “Many of the People of the Book wish to turn you back to disbelief out of envy, after the truth has become clear to them.” (Q 2:109)

The covenant thus shifts from a genealogical privilege to an ethical trust. This move perplexes and unsettles Jewish exclusivity because it means the covenant they guarded through Isaac reappears in Ishmael’s children — embodied in Muhammad ﷺ and his Ummah.

⸻

✦ Muhammad ﷺ and the Universalization of the Covenant

Abraham prayed:

“Our Lord, raise up from among them a Messenger, who will recite to them Your revelations, teach them the Book and wisdom, and purify them.”

(Q 2:129)

Muslims see Muhammad ﷺ as the direct fulfillment of this prayer. His Ummah, spread across nations, becomes Abraham’s true seed — the global nation of submission.

Thus, the Qur’an’s silence is purposeful: it avoids being trapped in ethnic polemics and instead establishes a covenant fulfilled through faith, not bloodline. This universality disarms rabbinic exclusivity and leaves Jewish scholars both perplexed and envious, as the covenantal promise “from the River of Egypt to the Euphrates” (Genesis 15:18) finds a broader expression in Islam’s spread.

⸻

✦ Conclusion

The Qur’an’s silences — on Hagar’s name, on the sacrificed son, on circumcision, and on Zamzam — are not omissions but theological strategies. They strip away tribal markers and redirect covenantal identity to submission to God.

Through this reframing, Muhammad ﷺ and his Ummah are established as the living heirs of Abraham’s covenant, fulfilling the patriarch’s universal mission. What once appeared as a lineage dispute is recast as a faith-based covenant — one that transcends genealogy and extends to all who submit to the God of Abraham.

🕋 ✝ Islam and Paul on the Abrahamic Covenant ✦ Ishmael, Isaac, and the Fulfillment of Faith

🔥 Who really inherits the promise of Abraham?

For over two thousand years, this question has divided believers. To Jews, the answer is Isaac, father of Israel. To Christians, following Paul, Isaac again becomes the key—but in a spiritualized sense, fulfilled in Christ. To Muslims, however, the heir is Ishmael, the firstborn son, consecrated through sacrifice and covenant, and the forefather of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

This is not just a matter of family tree—it’s about the very meaning of faith, law, and salvation. Islam and Paul tell two radically different stories about Abraham’s covenant, and those stories still shape how billions of people understand their relationship with God today.

⸻

Abraham (Ibrahim, عليه السلام) is one of the few figures who holds such a central position in the Abrahamic faiths. Revered as the friend of God, he embodies pure monotheism and the bearer of a covenant that continues to shape history. Yet the legacy of Abraham takes two very different paths in Islam and in the theology of Paul of Tarsus.

➤ In Islam, Ishmael (Ismāʿīl عليه السلام) is upheld as the true heir of the covenant.

➤ In Paul’s epistles, Isaac becomes the symbolic heir, while Ishmael is cast aside.

This is not a minor exegetical debate—it is a fundamental clash over lineage, covenant, and the meaning of salvation itself.

⸻

Abraham in Islam ✦ Ishmael as Covenant Heir

The Qur’an presents Abraham as chosen to lead humanity through his submission:

“Indeed, I will make you a leader for the people.”

Abraham asked, “And of my descendants?”

Allah replied, “My covenant does not include the wrongdoers.”

— Qur’an 2:124

✔ The covenant was universal and ethical, not restricted by ethnicity.

✔ Ishmael was alive when circumcision—the sign of the covenant—was established (Genesis 17:23–26). Isaac was not yet born.

✔ Abraham prayed for a prophet from Ishmael’s descendants (Qur’an 2:129), which Muslims believe was fulfilled in Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

Even the sacrifice story in Surah Aṣ-Ṣāffāt (37:100–113) aligns with Ishmael as the son offered—his submission alongside his father consecrated him as the rightful heir of Abraham’s mission.

⸻

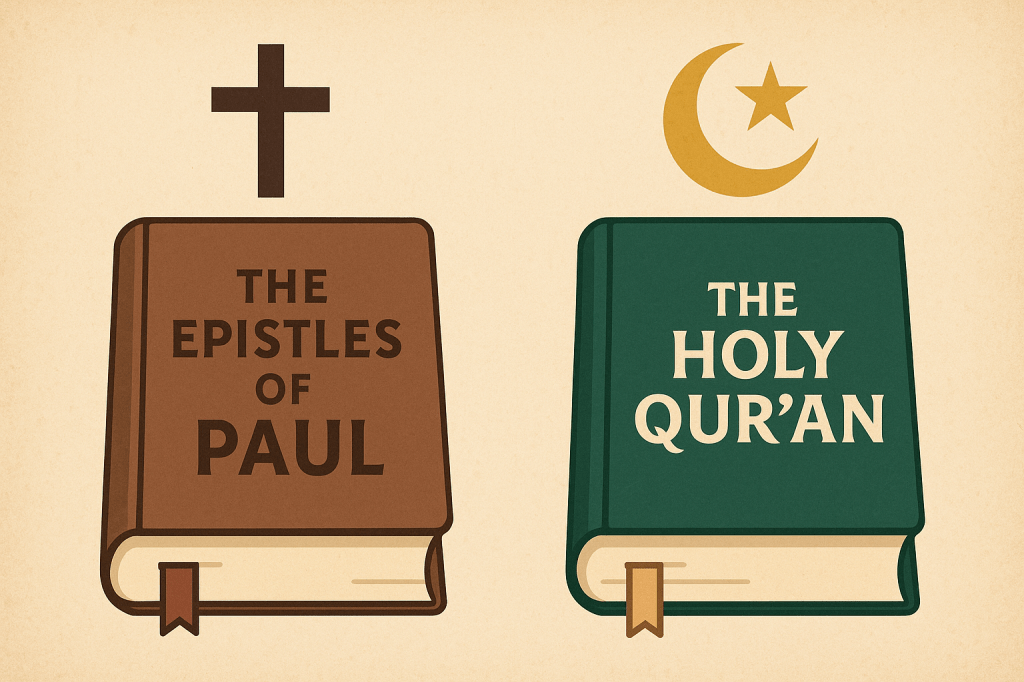

Paul’s Theology ✦ Faith and Isaac

Paul reframes Abraham’s covenant for a Gentile audience. His central claim: true heirs of Abraham are those who share his faith, not his bloodline.

✦ “Understand, then, that those who have faith are children of Abraham.” — Galatians 3:7

✗ Circumcision, Paul argues, is unnecessary. Abraham was justified by faith before being circumcised (Romans 4:9–11).

✗ In Galatians 4:21–31, Paul allegorizes the two sons:

• Ishmael = slavery, law, bondage.

• Isaac = freedom, promise, fulfillment in Christ.

Here, Paul reverses what Islam upholds: Ishmael is not heir but excluded, while Isaac is made central to salvation history.

⸻

The Sinai Covenant ✦ Broken or Temporary?

➤ Islam’s View:

• The Mosaic covenant was valid but conditional.

• Israel repeatedly broke it through disobedience (Qur’an 2:63, 5:13).

• Ultimately, God restored the Abrahamic covenant universally through the Qur’an and the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

➤ Paul’s View:

• The Law was never ultimate but only a temporary guardian (Galatians 3:24–25).

• With Christ, the covenant of grace supersedes the Law entirely.

• The Sinai covenant is not revoked for disobedience but rendered obsolete by design.

⸻

Key Contrasts ✦ Islam vs. Paul

✔ Covenant Heir

• Islam: Ishmael, consecrated through sacrifice and circumcision.

• Paul: Isaac, symbol of promise; Ishmael cast as bondage.

✔ Sign of Covenant

• Islam: Circumcision, first practiced by Abraham and Ishmael.

• Paul: Faith alone—ritual is secondary.

✔ Fulfillment of Covenant

• Islam: Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, descendant of Ishmael, restoring pure monotheism.

• Paul: Jesus Christ, descendant of Isaac, fulfilling promise through death and resurrection.

✔ Path to Salvation

• Islam: Submission (islām), obedience, and faith in one God.

• Paul: Grace through faith in Christ, apart from works of the Law.

⸻

Conclusion ✦ Competing Visions of Abraham’s Legacy

Islam and Paul stand on opposite sides of Abrahamic theology.

✦ Islam preserves Ishmael as heir, upholding the covenant through lineage, obedience, and the coming of Muhammad ﷺ.

✦ Paul spiritualizes the covenant, detaches it from law and ritual, and anchors it solely in faith through Christ.

At stake is more than which son was chosen—it is the very definition of what it means to be a true child of Abraham:

• In Islam: surrender to God’s will.

• In Paul’s theology: faith in Christ’s grace.

⸻

✨ This contrast continues to define how Islam and Christianity understand their Abrahamic roots—not merely as history, but as competing theological claims about covenant, salvation, and divine promise.

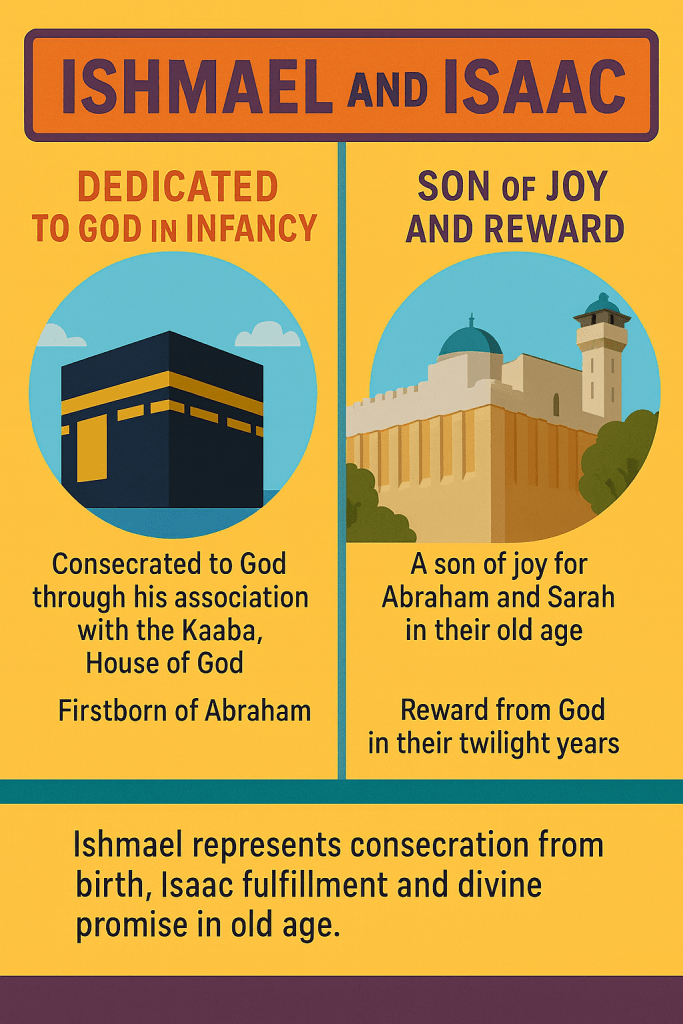

Ishmael and Isaac: Sons of Abraham, Different Paths of Dedication

Introduction

The story of Abraham’s two sons, Ishmael and Isaac, is central to the shared heritage of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. While both sons embody Abraham’s devotion to God, their roles and legacies differ in ways that shaped the theological horizons of nations. Ishmael represents consecration from infancy through his association with the Kaaba, the House of God, while Isaac stands as the son of joy and promise, born to Abraham and Sarah in their old age. Together, their stories reflect divine reward, human sacrifice, and covenantal destiny.

⸻

🔹 Ishmael: Consecrated in Infancy

According to Islamic tradition, Ishmael (Ismā‘īl عليه السلام) was dedicated to God from his earliest days. Abraham, at God’s command, left Hagar and infant Ishmael in the barren valley of Bakkah (later known as Mecca). This act was not abandonment but consecration: Ishmael was placed directly under God’s care, sustained by the miraculous spring of Zamzam.

The Kaaba, raised later by Abraham and Ishmael (Qur’ān 2:127–129), became the House of God on earth, a perpetual sign of Ishmael’s unique link to divine worship. Even the Bible hints at this sanctity when it states: “And God was with the child as he grew up” (Genesis 21:20). Ishmael, the firstborn, carried the sign of circumcision at thirteen, marking his flesh with the covenant long before Isaac was born. In this way, his entire life—from infancy onward—was devoted to God.

⸻

🔹 Isaac: The Son of Joy and Reward

Isaac (Isḥāq عليه السلام), by contrast, represents divine joy and fulfillment. Born when Abraham was a hundred and Sarah ninety, his very name (Yitzḥaq in Hebrew, “he laughs”) reflects the wonder and laughter of parents blessed in their old age. Isaac’s birth was not only a miracle but also a reward from God, granted after Abraham’s willingness to dedicate his firstborn son, Ishmael, upon the altar of sacrifice.

The Torah preserves God’s words: “Take your son, your only son…” (Genesis 22:2). While Jewish and Christian traditions identify Isaac as the son of this near-sacrifice, Islamic tradition regards Ishmael as the one tested. Moreover, Isaac’s name reflects grace and fulfillment, not trial and sacrifice.

⸻

🔹 Two Sons, One Covenant Story

Ishmael and Isaac embody two dimensions of Abraham’s devotion:

• Ishmael reflects consecration through sacrifice, hardship, and association with the House of God, Mecca. His line culminates in the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, through whom monotheism was universalized.

• Isaac reflects joy, blessing, and reward—proof that God fulfills promises even against natural odds. His line carries forward through Israel, the people who received the Law at Sinai.

Thus, the destinies of both sons form complementary expressions of the Abrahamic covenant: Ishmael sanctified from infancy, and Isaac gifted as a reward in old age. Together, they testify to God’s faithfulness, mercy, and the universality of His plan.

⸻

🔹 Conclusion

The lives of Ishmael and Isaac cannot be reduced to rivalry but must be understood as twin strands in Abraham’s legacy. Ishmael symbolizes the House of God in Mecca, consecration from birth, and the spiritual resilience of a firstborn offered to God. Isaac embodies joy, fulfillment, and divine promise in the twilight years of Abraham and Sarah. In their distinct paths, both sons reveal how God weaves dedication and reward into the fabric of covenant history—a story still alive in the hearts of Jews, Christians, and Muslims today.

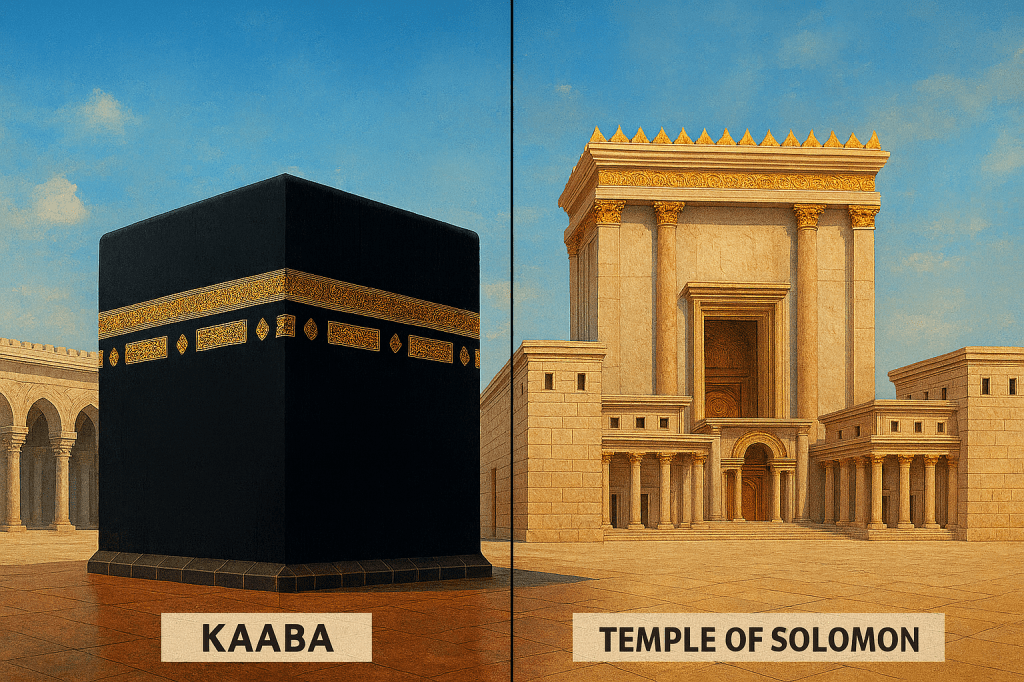

📜 Abraham, His Sons, and the House of God: A Comparative Study of the Bible and the Qur’an

🌟 Introduction

Across the Abrahamic traditions, the figure of Abraham stands as a foundational patriarch whose life, trials, and descendants shape the theological identity of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet the way these scriptures portray Abraham’s relationship to sacred places differs significantly. The Qur’an presents Abraham and his firstborn son Ishmael as the physical builders and consecrators of the Kaaba in Mecca. The Bible, in contrast, links Abraham and Isaac to the future Temple Mount through narrative association rather than construction. This distinction reveals how each tradition frames the origins of sacred space and the covenantal roles of Abraham’s sons.

⸻

♦️ 1. The Qur’an: Abraham, Ishmael, and the Kaaba

The Qur’anic narrative places Abraham (Ibrāhīm) and Ishmael (Ismāʿīl) at the centre of the establishment of the Kaaba, the primordial sanctuary in Mecca.

1.1 Building the Kaaba

The Qur’an explicitly describes Abraham and Ishmael raising the foundations of the Kaaba:

“And when Abraham raised the foundations of the House, and [with him] Ishmael, [saying], ‘Our Lord, accept this from us…’” (Qur’an 2:127)

This verse identifies them not only as worshippers but as architects of the House of God.

1.2 Dedication and Purification of the Sacred Space

Abraham and Ishmael are commanded to cleanse the House for those who perform worship, circumambulation, and devotion (Qur’an 2:125). Another passage speaks of Abraham leaving Ishmael’s descendants in the valley near the House to establish true worship (Qur’an 14:37), reinforcing their custodial role.

1.3 Universality of the Kaaba

The Qur’an describes the Kaaba as “the first House established for mankind” (Qur’an 3:96), giving it a universal, primordial character. Abraham and Ishmael thus appear not merely as historical figures but as founders of a sacred centre for all humanity.

In Islamic tradition, Abraham and Ishmael are understood as active constructors, purifiers, and guardians of the Kaaba — the earliest sanctuary dedicated to monotheistic worship.

⸻

♦️ 2. The Bible: Abraham, Isaac, and the Temple Mount

While the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh/Old Testament) also portrays Abraham as central to God’s covenantal plan, it does not attribute to him or to Isaac the establishment of a physical sanctuary.

2.1 Abraham and Isaac at Mount Moriah

Genesis 22 recounts the “Akedah,” or Binding of Isaac. God commands Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice “on one of the mountains in the land of Moriah” (Genesis 22:2).

Centuries later, 2 Chronicles 3:1 identifies this same region as the site of Solomon’s Temple:

“Then Solomon began to build the house of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord had appeared to David his father…”

This connection retroactively links the Akedah to the future Temple Mount. Yet the link is narrative and theological rather than architectural; Abraham and Isaac do not participate in constructing the sanctuary.

2.2 David and Solomon as Temple Builders

In the biblical tradition, the idea of a permanent sanctuary arises not with Abraham or Isaac but with King David. The Temple itself is built by Solomon (1 Kings 6), fulfilling David’s aspiration as narrated in 2 Samuel 7. Thus, temple-building is royal, not patriarchal.

⸻

♦️ 3. Key Difference: Builder vs. Symbol

A clear contrast emerges between the two scriptural traditions:

3.1 Qur’anic Perspective

• Abraham and Ishmael are direct builders and consecrators of the Kaaba.

• The sanctuary originates in their hands and through their supplication.

• The Kaaba becomes the focal point of monotheistic worship for all humanity.

3.2 Biblical Perspective

• Abraham and Isaac are linked to the site of the future Temple (Mount Moriah), but only symbolically.

• They do not build or establish a sanctuary.

• Temple-building is attributed to the Davidic-Solomonic monarchy.

3.3 Associative vs. Foundational

• The Bible connects Abraham and Isaac to the Temple through memory and location: the Akedah becomes part of Jerusalem’s sacred geography.

• The Qur’an connects Abraham and Ishmael to the Kaaba through construction and divine command: they physically establish the House of God.

⸻

♦️ Conclusion

Both the Bible and the Qur’an situate Abraham at the heart of sacred history, yet they portray his relationship to holy places in distinct ways. In the Qur’an, Abraham and Ishmael lay the physical and spiritual foundations of the Kaaba, making them architects of a universal sanctuary. In the Bible, Abraham and Isaac are remembered for their obedience at Moriah, a site later reinterpreted as the location of the Temple, but they do not build it.

These contrasting narratives shape how each tradition understands sacred space, lineage, and the enduring legacy of Abraham and his sons.