Azahari Hassim

🔹 Ishmael and Isaac: Sons of Abraham, Different Paths of Dedication

Introduction

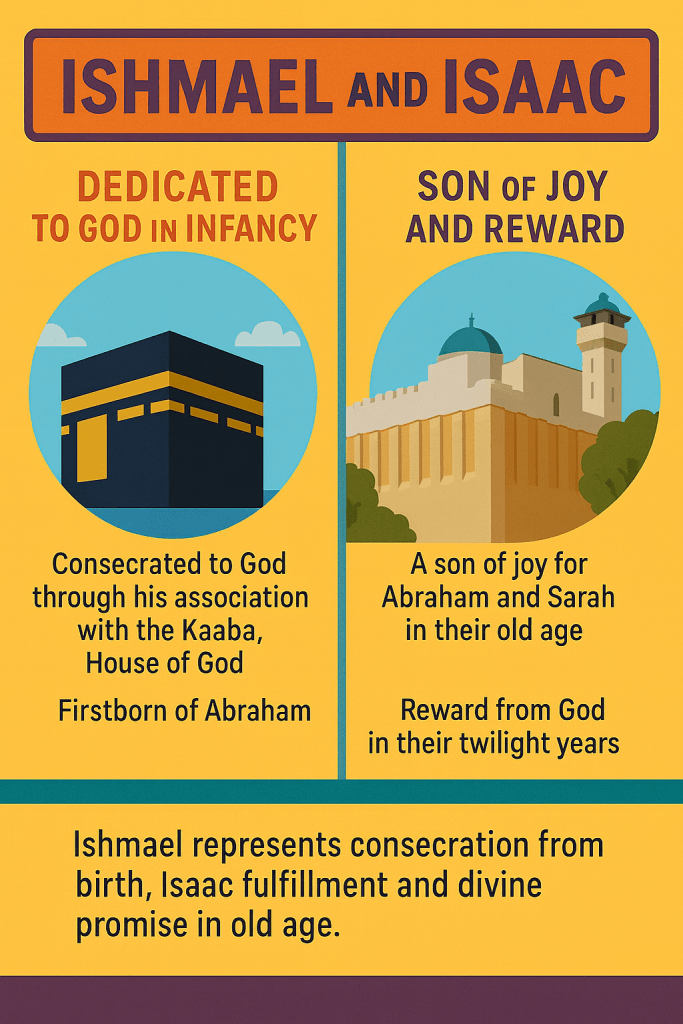

The story of Abraham’s two sons, Ishmael and Isaac, is central to the shared heritage of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. While both sons embody Abraham’s devotion to God, their roles and legacies differ in ways that shaped the theological horizons of nations. Ishmael represents consecration from infancy through his association with the Kaaba, the House of God, while Isaac stands as the son of joy and promise, born to Abraham and Sarah in their old age. Together, their stories reflect divine reward, human sacrifice, and covenantal destiny.

⸻

🔹 Ishmael: Consecrated in Infancy

According to Islamic tradition, Ishmael (Ismā‘īl عليه السلام) was dedicated to God from his earliest days. Abraham, at God’s command, left Hagar and infant Ishmael in the barren valley of Bakkah (later known as Mecca). This act was not abandonment but consecration: Ishmael was placed directly under God’s care, sustained by the miraculous spring of Zamzam.

The Kaaba, raised later by Abraham and Ishmael (Qur’ān 2:127–129), became the House of God on earth, a perpetual sign of Ishmael’s unique link to divine worship. Even the Bible hints at this sanctity when it states: “And God was with the child as he grew up” (Genesis 21:20). Ishmael, the firstborn, carried the sign of circumcision at thirteen, marking his flesh with the covenant long before Isaac was born. In this way, his entire life—from infancy onward—was devoted to God.

⸻

🔹 Isaac: The Son of Joy and Reward

Isaac (Isḥāq عليه السلام), by contrast, represents divine joy and fulfillment. Born when Abraham was a hundred and Sarah ninety, his very name (Yitzḥaq in Hebrew, “he laughs”) reflects the wonder and laughter of parents blessed in their old age. Isaac’s birth was not only a miracle but also a reward from God, granted after Abraham’s willingness to dedicate his firstborn son, Ishmael, upon the altar of sacrifice.

The Torah preserves God’s words: “Take your son, your only son…” (Genesis 22:2). While Jewish and Christian traditions identify Isaac as the son of this near-sacrifice, Islamic tradition regards Ishmael as the one tested. Moreover, Isaac’s name reflects grace and fulfillment, not trial and sacrifice.

⸻

🔹 Two Sons, One Covenant Story

Ishmael and Isaac embody two dimensions of Abraham’s devotion:

• Ishmael reflects consecration through sacrifice, hardship, and association with the House of God, Mecca. His line culminates in the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, through whom monotheism was universalized.

• Isaac reflects joy, blessing, and reward—proof that God fulfills promises even against natural odds. His line carries forward through Israel, the people who received the Law at Sinai.

Thus, the destinies of both sons form complementary expressions of the Abrahamic covenant: Ishmael sanctified from infancy, and Isaac gifted as a reward in old age. Together, they testify to God’s faithfulness, mercy, and the universality of His plan.

⸻

🔹 Conclusion

The lives of Ishmael and Isaac cannot be reduced to rivalry but must be understood as twin strands in Abraham’s legacy. Ishmael symbolizes the House of God in Mecca, consecration from birth, and the spiritual resilience of a firstborn offered to God. Isaac embodies joy, fulfillment, and divine promise in the twilight years of Abraham and Sarah. In their distinct paths, both sons reveal how God weaves dedication and reward into the fabric of covenant history—a story still alive in the hearts of Jews, Christians, and Muslims today.

🕊️ A Nontraditional Chronological Reading of Genesis: Ishmael’s Role in the Sequence of Covenants

This argument represents a nontraditional chronological reading of Genesis that seeks to reconcile narrative and covenantal tensions surrounding Abraham, Ishmael, and Isaac. It reorders the events to portray Ishmael—not Isaac—as the son tested in the near-sacrifice episode, interpreting Genesis as a progressive unfolding of divine trials and covenantal ratifications.

➤ 1. Premise: The Covenants and Promises Are Sequentially Related

Proponents begin by noting that Genesis presents several covenantal moments with Abraham—particularly in Genesis 15, Genesis 17, Genesis 21, and Genesis 22—which they view as successive stages of a single divine plan rather than separate, unrelated episodes.

★ Genesis 15: God promises Abraham descendants as numerous as the stars.

★ Genesis 17: God formalizes this promise through the covenant of circumcision, renaming Abram as Abraham, “father of many nations.”

★ Genesis 21:14–20: Abraham faces his first test concerning Ishmael’s fate when Hagar and Ishmael are sent away into the wilderness.

★ Genesis 22: Abraham faces the ultimate test—offering his “only son” to God.

In this interpretive model, the episodes are not arranged chronologically in the canonical order. Genesis 21 and 22, both dealing with Ishmael, are understood to precede Genesis 17, forming the experiential foundation upon which the covenant of circumcision is later ratified.

➤ 2. Genesis 22 — The Supreme Test: Abraham’s Willingness to Sacrifice Ishmael

In the canonical order, Genesis 22 features the near-sacrifice of Isaac. But the description of the son as “your only son” cannot apply to Isaac if Ishmael is alive and older. By placing Genesis 22 earlier—before Isaac’s conception—the narrative unfolds with perfect coherence:

• Ishmael is Abraham’s firstborn.

• Ishmael is Abraham’s only son at that stage.

• Ishmael is the son through whom Abraham has already received divine promises.

Thus, in non-canonical interpretations where Genesis 22 precedes Genesis 17, the son offered in the near-sacrifice must be Ishmael, since Isaac had not yet been born or even promised.

➤ 3. Genesis 21:14–20 as the First Test of Abraham

Before the near-sacrifice in Genesis 22, the episode in Genesis 21:14–20 portrays Abraham’s earlier emotional trial involving Ishmael. In this narrative, Abraham sends Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness at Sarah’s insistence. The text describes Ishmael as an infant carried by Hagar, a detail that aligns closely with the Islamic tradition in which Ishmael is still a small child when Abraham leaves him in the desert (Mecca).

According to Genesis 21:5, Ishmael would have been 16–17 years old at the time. Yet the surrounding verses (vv. 14–20) treat him as if he were a helpless toddler. This is not merely a literary flourish but a direct inconsistency in age and behavior within the same episode.

Therefore, in non-canonical interpretations, Genesis 21:14–20 is understood to occur prior to Genesis 17—specifically because the passage depicts Ishmael as an infant or small child, in stark contrast to Genesis 17, which explicitly states that Ishmael was already 13 years old. By placing the desert episode before Genesis 17, the age contradiction is resolved, and the narrative fits naturally within an earlier phase of Abraham’s life.

Viewed this way, the “banishment test” becomes Abraham’s first trial involving Ishmael, testing his faith in God’s promise concerning Ishmael’s survival and future greatness (“I will make him a great nation,” Gen 21:18).

The subsequent “sacrifice test” in Genesis 22 then functions as the second and supreme trial, where Abraham’s obedience reaches its deepest expression. Together, these two Ishmael-centered episodes frame the development of Abraham’s faith before the covenantal ratification of Genesis 17.

➤ 4. Identification of the Sacrificed Son as Ishmael

On this reordered chronology:

★ The “only son” of Genesis 22 refers to Ishmael, Abraham’s firstborn by Hagar.

★ The phrase “your son, your only son” (Gen 22:2) fits Ishmael prior to Isaac’s birth.

★ The later introduction of Isaac (Gen 17–18) is not a replacement but a continuation of the divine plan—rewarding Abraham’s faithfulness through a second lineage that expands the original covenant.

Hence, the Akedah (binding of the son) becomes a test of Ishmael’s line, and Genesis 17 becomes a ratification of that obedience through the promise of “many nations.”

➤ 5. Genesis 17 as Covenant Ratification

In this model, Genesis 17 does not precede but follows the tests of Genesis 21–22. It represents God’s ratification of Abraham’s proven obedience:

★ Abraham is renamed and blessed as “father of many nations.”

★ Circumcision is introduced as a covenantal sign, extending the promise to all his progeny.

★ The birth of Isaac is announced as a reward and continuation of divine favor.

Thus, Genesis 17 serves as the formalization of the faith demonstrated earlier through Abraham’s trials involving Ishmael.

➤ 6. Literary-Critical Perspective

From a literary-critical standpoint, this interpretation draws upon source-critical and redactional insights. Scholars employing the Documentary Hypothesis often distinguish between several compositional layers within Genesis, each reflecting different theological emphases and historical contexts:

★ Genesis 21 and Genesis 22 are generally attributed to the Elohist (E) and Jahwist (J) sources, which are earlier traditions. These sources emphasize vivid narrative, moral testing, and divine encounter—often conveyed through the figure of the angel of the Lord.

★ Genesis 17, by contrast, is assigned to the Priestly (P) source, which is later in composition and is marked by formal covenantal language, ritual precision, and theological systematization.

Within this framework, proponents of the chronological reordering argue that the older E/J traditions—which may have originally centered on Ishmael—were subsequently integrated and reinterpreted by Priestly editors. These later redactors inserted Genesis 17’s covenantal structure before the narrative of Genesis 22, thereby reshaping the sequence to emphasize Isaac as the covenantal heir.

Thus, from a literary-critical perspective, the hypothesis that Genesis 22 predates Genesis 17 in origin aligns with the idea that an earlier Ishmaelite-focused narrative was overlaid by a later Priestly redaction, producing the canonical order familiar today.

➤ 7. Summary Articulation

To summarize:

★ 1. Genesis 21:14–20 presents Abraham’s first test concerning Ishmael’s separation, aligning with the Islamic account of the desert episode.

★ 2. Genesis 22 (the near-sacrifice) represents the second and climactic test, also involving Ishmael.

★ 3. Genesis 17, announcing Isaac’s birth and instituting circumcision, follows these trials and serves as God’s ratification of Abraham’s faith.

Therefore, the sequence Genesis 21 → Genesis 22 → Genesis 17 portrays a coherent theological and narrative progression in which Abraham’s obedience regarding Ishmael becomes the foundation for his establishment as the “father of many nations.”

This reading not only restores textual coherence to the phrase “your only son,” but also resolves the age contradiction, places the narrative within an earlier phase of Abraham’s life, integrates Ishmael’s covenantal significance, and provides a bridge between Biblical and Qur’anic portrayals of Abraham’s faith.

📖 Ishmael in Genesis 21: Baby vs. Mocking Teenager

Hagar and Ishmael cast out, as in Genesis 21, illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible.

This black-and-white engraving depicts the biblical scene of Hagar and Ishmael being cast out. A sorrowful Hagar is shown leading her young son Ishmael by the arm, walking barefoot and carrying provisions. Ishmael looks distressed, while Hagar appears contemplative and burdened. In the background, Abraham and Sarah can be seen near the doorway of a house—Sarah holding Isaac—emphasizing the cause of the expulsion. The illustration captures the pathos of separation and exile central to the Genesis 21 narrative.

✍️ A Case for Interpolation in Genesis 21:9–10

⸻

⚖️ The Core Contradiction

Genesis 21 contains two irreconcilable portrayals of Ishmael:

• Genesis 21:14–20 → Ishmael is depicted as a helpless child—carried on Hagar’s shoulder, laid under a bush, and rescued by an angel. Verse 20 reinforces this image: “And God was with the boy, and he grew.” If Ishmael had already been a teenager or older, it would not have been necessary to mention his growth.

• Genesis 21:9–10 → Ishmael appears as a teenager “mocking” Isaac, prompting Sarah to demand his expulsion to secure Isaac’s inheritance.

But according to Genesis 16:16 and 21:5, Ishmael was 16–17 years old at this point. The surrounding verses (vv. 14–20), however, treat him as if he were an infant. This is not a stylistic flourish but a direct contradiction in age and behavior within the same episode.

⸻

📜 The Textual Inconsistency

The contradiction is sharp:

• 👶 Genesis 21:14–20 + 21:20 → Ishmael is a small boy growing up under God’s care.

• 🧑🦱 Genesis 21:9–10 → Ishmael is a mocking adolescent, a threat to Isaac’s status.

This inconsistency strongly suggests that Genesis 21 combines two traditions or has been redacted with an interpolation to reshape the story.

⸻

🔎 Why 21:9–10 is Interpolation

Several factors converge:

- ⚖️ Contradictory portrayals: helpless child vs. mocking teenager.

- ⚡ Abrupt insertion: v. 9 introduces a sudden and unexplained motive.

- 📖 Theological shaping: vv. 9–10 are designed to exclude Ishmael from inheritance.

- 📚 Textual fluidity: the LXX shows this very section was unstable.

- 🧵 Narrative flow without vv. 9–10: the story reads smoothly if Sarah’s demand is absent—Abraham provides, Hagar departs, baby Ishmael nearly dies, God rescues, Ishmael grows.

⸻

✡️ Hebrew Note

In Genesis 21:14, the Hebrew says:

וַיִּתֵּ֣ן אֶל־הָגָ֑ר שָׂ֣ם עַל־שִׁכְמָ֔הּ וְאֶת־הַיֶּ֖לֶד

“He put [the bread and water] on her shoulder, and [he gave her] the child.”

Some translations smooth this as if Abraham “placed the child on her shoulder,” reinforcing the infant image. Others take it as “gave her the child,” but the syntax still suggests dependence and smallness—clashing with the teenager portrayal of vv. 9–10.

⸻

☪️ The Islamic Resonance

The “helpless child” imagery in Genesis 21 aligns closely with the Islamic tradition, in which Abraham leaves Hagar and infant Ishmael in the valley of Makkah, where God miraculously provides water (the well of Zamzam 💧).

This suggests that the older stratum of the story remembered Ishmael as a baby. The later interpolation (vv. 9–10) reframes him as a rival heir to justify his expulsion and Isaac’s primacy.

⸻

✅ Conclusion

Genesis 21 preserves two incompatible portrayals of Ishmael:

• 👶 one as a baby in need of rescue (vv. 14-20),

• 🧑 one as a mocking teenager (vv.9-10).

The tension is best explained by redactional activity, with Genesis 21:9–10 functioning as an interpolation to serve Israel’s covenantal theology.

Without those verses, the passage regains coherence and aligns with an earlier tradition—one that resonates strongly with the Islamic account of Ishmael’s infancy.

Isaac or Ishmael? A Comparative Study of the Abrahamic Covenant in Islam and the Bible

- Why Islamic Scholars Believe the Torah Was Altered Regarding Ishmael

The Qur’an accuses some Jewish scribes of altering scripture:

“Do you hope they will believe you, when some of them used to hear the words of God then distort them after they had understood them, knowingly?” (Qur’an 2:75)

“So woe to those who write the Book with their own hands and then say, ‘This is from God,’ to exchange it for a small price.” (Qur’an 2:79)

This doctrine of taḥrīf (distortion) is applied by Muslim exegetes to the Abrahamic covenant narratives. They argue that the Torah originally gave Ishmael covenantal prominence, but Jewish scribes altered the text to place Isaac in that role for political and ethnic reasons:

• Ethnic exclusivity: Restricting the covenant to Isaac made it Israel’s exclusive inheritance.

• Religious authority: Elevating Isaac justified Israel’s claim to be God’s sole chosen people.

• Arab-Israelite rivalry: Excluding Ishmael delegitimized the Ishmaelites (later Arabs) as covenantal heirs.

⸻

- Islamic Reasons Supporting Ishmael’s Role

a. Qur’anic Testimony

• Universal covenant: Abraham was promised leadership for his descendants, but God limited it to the righteous, not by bloodline (Qur’an 2:124). Ishmael qualifies.

• The Sacrifice Narrative: Qur’an 37:101–112 implies the sacrificed son was Ishmael, since Isaac’s birth is mentioned after the sacrifice story.

• Kaaba (House of God) and prayer for Ishmael’s descendants: Abraham and Ishmael built the Kaaba and prayed for a messenger from their line (Qur’an 2:127–129) — fulfilled in Muhammad ﷺ.

• Praise for Ishmael: The Qur’an honors Ishmael as a prophet and covenant-keeper (Qur’an 19:54–55).

b. Historical logic

• Firstborn son: By ancient Near Eastern custom, Ishmael (the firstborn) should have been covenantal heir unless disqualified — but the Bible itself shows God blessing him greatly (Genesis 17:20).

• Circumcision: Ishmael was circumcised at the age of 13, on the same day as his father Abraham, and before Isaac was born (Genesis 17:23–25). This means that Ishmael entered the covenant earlier than Isaac. Therefore, the theological importance of Isaac’s circumcision is similar to that of the other members of Abraham’s household.

• Sacrificial test: Islam preserves Ishmael’s central role in the great test of faith, commemorated annually at Eid al-Adha. Judaism and Christianity, in contrast, have no liturgical commemoration of Isaac’s binding (Akedah), which Muslims see as a sign of textual alteration.

⸻

- Biblical Reasons that Support the Islamic Assertion

Even within the Bible, there are tensions and clues that suggest Ishmael’s role was more significant than later scribes allowed:

- Ishmael is blessed to become a “great nation”

• “As for Ishmael, I have heard you. I will surely bless him; I will make him fruitful and will greatly increase his numbers. He will be the father of twelve rulers, and I will make him into a great nation.” (Genesis 17:20)

This blessing closely parallels covenantal promises given to Isaac. - Circumcision before Isaac

• Genesis 17:23–25 explicitly records Ishmael’s circumcision as covenantal sign, before Isaac’s birth. This raises the question: why would the covenant sign be given to one excluded from it? - Ambiguity of the Sacrifice Story

• In Genesis 22:2, Isaac is named as the son to be sacrificed. But Muslim scholars argue this insertion is suspicious because:

• Earlier verses (Genesis 22:1) simply say “your son, your only son” — which could only have referred to Ishmael at the time, since Isaac wasn’t born until later.

• The phrase “your only son” makes no sense if Isaac is meant, because Ishmael was alive. Thus, the text seems edited. - No Jewish Festival for the Binding

• Despite its centrality, Judaism has no feast commemorating Isaac’s binding, whereas Islam preserves its memory through Eid al-Adha. This absence suggests the Isaac-centered version was secondary. - Arab traditions of Abraham and Ishmael

• Pre-Islamic Arabs preserved traditions of Abraham and Ishmael at the Kaaba (House of God) in Mecca. This continuity indicates Ishmael’s role was widely remembered outside of Jewish editing.

⸻

4. Ishmael as a Baby: A Biblical Contradiction

The book of Genesis presents Ishmael in a way that appears inconsistent with the chronological details of the narrative:

• Genesis 21:9–10: Sarah sees “the son of Hagar” and demands that Abraham “cast out” the slave woman and her son. Ishmael would have been approximately 16 or 17 years old at this point — not a small child.

• Genesis 21:14–18: Abraham sends Hagar away with bread and water, placing the child on her shoulder as though he were an infant. Later, Hagar lays Ishmael under a bush, unable to watch him die of thirst, until an angel instructs her to “lift the boy up.”

• Genesis 21:20: The text continues, “And God was with the boy as he grew,” which further suggests an image of early childhood.

However, according to the timeline (Genesis 16:16; 21:5), Ishmael would have been approximately 16–17 years old at this stage. The portrayal of him as a helpless baby, therefore, introduces a notable tension within the biblical narrative.

Interestingly, this depiction parallels the Islamic account, which holds that Ishmael was still an infant when Hagar left Abraham’s household and settled in the valley of Makkah, where God provided for them. From this perspective, the biblical image of Ishmael as a young child—despite its chronological inconsistencies—can be seen as indirectly reinforcing the Islamic tradition that situates his departure during infancy, long before the birth of Isaac.

Furthermore, some scholars view Genesis 21:9–10, where Sarah insists on the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael, as a later editorial addition. This insertion may have been intended to emphasize Isaac as the legitimate covenant heir and to reduce Ishmael’s significance, thereby reinforcing Israel’s unique identity within the biblical narrative.

⸻

Conclusion

The ambiguous wording of the sacrifice narrative—where the phrase “your son, your only son” could only have referred to Ishmael at that time—and the fact that Ishmael was circumcised alongside Abraham before Isaac’s birth, strongly indicate his covenantal significance. These elements suggest that Ishmael was indeed a rightful heir of the Abrahamic covenant, but the text was later shaped to elevate Isaac while diminishing Ishmael’s original role.

The contradictions within Genesis — portraying Ishmael as both a teenager by chronology and as a helpless baby by narrative — point to possible textual reshaping intended to diminish his stature in favor of Isaac. At the same time, this very imagery, whether intentional or not, indirectly supports the Islamic belief that Ishmael was in fact an infant when he left Abraham’s household with Hagar.

Islam affirms that Ishmael was never rejected. Instead, he was a prophet, covenant-bearer, and forefather of Muhammad ﷺ. Through him, the Abrahamic covenant found its universal fulfillment, not confined to one lineage but extending to all nations through Muhammad and the message of Islam.