Azahari Hassim

📦🕋 The Ark of the Covenant and the Kaaba: Two Stages of God’s Covenantal Unfolding in Islamic Perspective

Introduction

In the history of Abrahamic faiths, sacred objects and sanctuaries have often served as visible signs of God’s covenant with humankind. From an Islamic perspective, both the Ark of the Covenant and the Kaaba (House of God) represent distinct stages in the unfolding of divine history.

The Ark embodied the Sinai covenant, centered upon the Law revealed to Moses (Mūsā عليه السلام), while the Kaaba, constructed by Abraham (Ibrāhīm عليه السلام) and Ishmael (Ismāʿīl عليه السلام), stands as the enduring symbol of the universal covenant of monotheism. These two symbols—one lost to history, the other preserved and revered—reflect the transition from particularity to universality in God’s plan for humanity.

The Ark of the Covenant and the Sinai Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant held a central role in Israelite religion. Described in the Hebrew Bible as a gilded wooden chest containing the tablets of the Law (Exodus 25:10–22), it served as the visible sign of God’s presence among the Children of Israel. The Ark was housed first in the Tabernacle and later in the Temple of Solomon, representing the covenant God made with Israel at Mount Sinai.

From an Islamic perspective, this covenant was real and significant but limited in scope. It was tied to a particular people, a priestly class, and a sacred geography centered upon Jerusalem. The Qur’an itself acknowledges that God honored Israel and entrusted them with divine guidance (Qur’an 2:47–53).

However, it also records how this covenant was frequently broken, and how the Israelites often strayed from God’s commands (Qur’an 2:63–64). Ultimately, the Ark—so central to their religious life—was lost to history, symbolizing the fragility of a covenant confined to one nation and dependent on physical objects.

The Kaaba and the Abrahamic Covenant

By contrast, the Kaaba stands as a universal symbol of God’s covenant with humankind. According to Islamic tradition, Abraham and Ishmael were commanded to raise the foundations of the Kaaba as a sanctuary for the worship of the One God (Qur’an 2:125–129). Unlike the Ark, which was portable and hidden within the Holy of Holies, the Kaaba was established as a permanent sanctuary, accessible to all who respond to the call of Abraham:

“Proclaim the pilgrimage to all people—they will come to you on foot and on every lean camel, from every distant path.”

(Qur’an 22:27)

The Kaaba thus universalizes the Abrahamic covenant. It is not confined to one people or priesthood but welcomes nations and tribes from across the earth. It serves as the qibla (direction of prayer) for Muslims worldwide, embodying the unity of humankind in submission to Allah.

Continuity and Fulfillment

The contrast between the Ark and the Kaaba illustrates the unfolding of divine history. The Ark symbolized the Sinai covenant—a covenant of law, priesthood, and nationhood. The Kaaba symbolizes the Abrahamic covenant fulfilled in Islam—a covenant of faith, unity, and universality. Where the Ark was lost, the Kaaba endures; where the Ark excluded all but a priestly elite, the Kaaba is open to all believers; where the Ark tied covenantal life to a single people, the Kaaba extends God’s invitation to the entire human family.

Conclusion

From an Islamic perspective, the Ark of the Covenant and the Kaaba represent two stages of God’s covenantal unfolding. The Ark was associated with the Sinai covenant, which was specific in scope and tied to Israel; however, its historical significance was not enduring.

The Kaaba, by contrast, embodies the universal call of the Abrahamic covenant, preserved through Islam and accessible to all who affirm the oneness of God. It endures as a living sanctuary, welcoming nations to renew their bond with the Creator and to walk in the path of Abraham, the patriarch of monotheism.

📜 Until Shiloh Comes: The Transfer of Covenant from Sinai to Abraham through Ishmael

Introduction

🌟 Genesis 49:10 stands as one of the most profound prophecies in the Hebrew Bible, where Jacob’s blessing to Judah speaks of a mysterious figure called “Shiloh”. For centuries, both Jewish and Christian traditions have understood this verse as messianic, anticipating a redeemer from Judah’s lineage.

However, when examined through the wider lens of covenantal theology, this verse reveals a deeper transition — from the Sinai covenant, particular to Israel and bound by Mosaic law, to the Abrahamic covenant, universal in scope and ultimately fulfilled through Ishmael’s descendants.

This article explores how the prophecy of “Shiloh” may refer not to a ruler from Judah, but to a divinely appointed messenger from Ishmael’s descendants, through whom the Abrahamic faith reaches its completion and universality in the message of Islam.

This perspective recognizes that it was Ishmael, not Isaac, whom God commanded Abraham to offer in sacrifice — the supreme act of submission that sealed Abraham’s faith. This event, memorialized every year by Muslims in the festival of Eid al-Adha, signifies the enduring covenant through Ishmael’s line, culminating in the coming of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, the promised Shiloh through whom divine guidance attained its universal form.

—

1. The Context of Jacob’s Prophecy

In Genesis 49, Jacob gathers his twelve sons and speaks of their future destinies. Concerning Judah, he declares:

“The scepter shall not depart from Judah,

nor a lawgiver from between his feet,

until Shiloh comes; and to him shall the obedience of the peoples be.”

(Genesis 49:10)

Traditionally, this prophecy has been interpreted as predicting Judah’s enduring leadership until the arrival of a messianic ruler. Yet a covenantal reading reveals that this marks not permanence but transition — from Judah’s temporal authority under the Sinai covenant to the restoration of the Abrahamic covenant through Ishmael, the son of sacrifice and obedience.

Several scholars believe that the word “until” in the verse indicates the time at which Judah’s authority ended.

Therefore, Shiloh (Messiah) does not descend from David’s lineage, which is traced back to Judah.

—

2. The Scepter and Lawgiver: Symbols of the Sinai Covenant

The first half of the verse — “The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet” — symbolizes the religious and political authority vested in Judah.

The scepter represents kingship, embodied in David and his royal line.

The lawgiver refers to the Torah, the revealed law of Sinai that governed Israel’s covenantal life.

This Sinaitic covenant was conditional and particular, bound to a specific nation and land. It endured “until Shiloh came” — until divine authority passed to the heir of Abraham’s universal covenant through Ishmael.

—

3. Shiloh and the Renewal of the Abrahamic Covenant through Ishmael

The word Shiloh carries meanings such as peace, rest, or he whose right it is. It thus designates the rightful inheritor of divine authority.

In the story of Abraham’s supreme test, as preserved in Islamic tradition, Ishmael is the son chosen for sacrifice — the act that confirmed both Abraham’s faith and Ishmael’s submission. In recognition of this, God renewed His promise:

“As for Ishmael, I have blessed him, and will make him fruitful, and will multiply him exceedingly; twelve princes shall he beget, and I will make him a great nation.”

(Genesis 17:20)

This promise is inseparable from the earlier Abrahamic benediction in Genesis 22:18:

“And in your seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because you have obeyed My voice.”

From an Islamic perspective, this universal blessing reaches its perfection in Shiloh — the divinely appointed messenger from Ishmael’s descendants, Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, through whom the Abrahamic faith was universalized beyond lineage and territory.

—

4. Shiloh as the Prophet from Ishmael’s Descendants

In the Islamic understanding, Shiloh points to Muhammad ﷺ, the final messenger and restorer of Abrahamic monotheism.

The scepter and lawgiver symbolize Judah’s rule under the Mosaic order, which lasted until Shiloh’s advent.

The arrival of Shiloh marks the transfer of divine covenant from a national to a universal dispensation.

The phrase “and to him shall the obedience of the peoples be” finds its fulfillment in the global ummah united in Islam.

Through Muhammad ﷺ, the two branches of Abraham’s family — Isaac and Ishmael — converge in spiritual unity, as the promise made on the mountain of sacrifice finds its universal realization.

This fulfills the Abrahamic prophecy of Genesis 22:18 — “in your seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed” — echoed centuries later in the Qur’anic verse:

“And We have not sent you except as a mercy to all the worlds.”

(Surah 21:107)

The blessing to “all nations” in Genesis thus finds its full resonance in the Qur’an’s rahmah lil-‘ālamīn — mercy to the worlds.”

—

5. The Living Memory of the Covenant: Eid al-Adha

The memory of Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Ishmael is not a forgotten legend. It is commemorated annually by Muslims worldwide in the sacred festival of Eid al-Adha (“The Feast of Sacrifice”).

Each year, millions of believers retrace Abraham’s obedience by offering sacrifices in remembrance of his willingness to surrender his beloved son at God’s command. This universal observance — transcending race, nation, and language — is the living embodiment of the Abrahamic covenant through Ishmael, reaffirming humanity’s submission (Islām) to the One God.

Through Eid al-Adha, the covenant of faith, obedience, and trust in divine will is renewed across generations — a perpetual testimony that the legacy of Abraham and Ishmael remains alive within the heart of the Muslim community.

—

6. The Biblical and Qur’anic Continuity

The Qur’an reaffirms this covenantal unity:

“Were you witnesses when death approached Jacob, when he said to his sons:

‘What will you worship after me?’

They said: ‘We will worship your God, and the God of your fathers — Abraham, Ishmael, and Isaac — One God, and to Him we submit.’”

(Qur’an 2:133)

Here, Ishmael stands explicitly alongside Abraham and Isaac as a patriarch of covenantal faith, confirming that divine favor is not ethnic but spiritual — a continuity of submission to the Creator.

—

7. The Transfer of Covenant and Authority

The New Testament, too, preserves a hint of this covenantal transition. Jesus proclaimed:

“And I say unto you, that many shall come from the east and west, and shall sit down with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven.

But the children of the kingdom shall be cast out into outer darkness: there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

(Matthew 8:11–12)

This declaration signifies a divine realignment of covenantal authority. The “children of the kingdom” — those who claimed exclusive descent from Israel — would lose their privileged position, while “many from the east and west” would inherit the covenantal blessings by embracing the faith of Abraham.

From an Islamic perspective, this imagery points to the emergence of a new spiritual community beyond ethnic or national boundaries — the ummah of Islam — gathered from all directions of the earth. It is this global assembly of believers, united in the submission (Islām) that characterized Abraham himself, who truly “sit with Abraham” in the renewed Kingdom of Heaven.

In the Abrahamic continuum, this renewal is realized through Ishmael’s descendants, led by Muhammad ﷺ, the promised Shiloh, through whom the covenant finds its universal completion. Thus, the “Kingdom of Heaven” in Jesus’ saying can be seen as the restored Abrahamic faith of submission, embodied and perfected in Islam.

—

8. From Sinai to Mecca: The Completion of the Covenant

The geography of revelation reflects this sacred progression:

From Mount Sinai, where the Law was given to Moses;

To Mount Zion, where David ruled over Israel;

To the Sanctuary of Mecca, where Muhammad ﷺ restored the House of Abraham.

Thus, revelation moves from law to faith, from tribe to humanity, from Sinai to Mecca. The coming of Shiloh from Ishmael’s line fulfills the Abrahamic promise in its universal form, making Islam the completion of the covenant’s long journey — the very fulfillment of Genesis 22:18 and Surah 21:107 united in one divine truth.

—

9. Conclusion

Genesis 49:10 encapsulates the divine drama of covenantal history — the passing of the scepter of revelation from Judah’s temporal rule to Ishmael’s enduring spiritual lineage.

For the Jews, Shiloh remains the awaited Messiah.

For Christians, he prefigures Christ.

But for Muslims, he is Muhammad ﷺ — the promised Shiloh, the Seal of Prophethood, and the descendant of Ishmael, whose submission on the altar of sacrifice became the symbol of perfect faith.

Every year, the world’s Muslim community renews this covenant through Eid al-Adha, keeping alive the memory of Abraham’s trial and Ishmael’s obedience. Through that living tradition, the promise of Genesis 22:18 — “in your seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed” — finds its full realization in the Qur’an’s affirmation:

“And We have not sent you except as a mercy to all the worlds.”

(Surah 21:107)

Thus, the Abrahamic covenant, universalized through Ishmael and fulfilled in Muhammad ﷺ, stands as the enduring testament that divine mercy, guidance, and covenantal blessing belong to all humankind.

📜 Abraham, His Sons, and the House of God: A Comparative Study of the Bible and the Qur’an

🌟 Introduction

Across the Abrahamic traditions, the figure of Abraham stands as a foundational patriarch whose life, trials, and descendants shape the theological identity of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet the way these scriptures portray Abraham’s relationship to sacred places differs significantly.

The Qur’an presents Abraham and his firstborn son Ishmael as the physical builders and consecrators of the Kaaba in Mecca. The Bible, in contrast, links Abraham and Isaac to the future Temple Mount through narrative association rather than construction. This distinction reveals how each tradition frames the origins of sacred space and the covenantal roles of Abraham’s sons.

⸻

♦️ 1. The Qur’an: Abraham, Ishmael, and the Kaaba

The Qur’anic narrative places Abraham (Ibrāhīm) and Ishmael (Ismāʿīl) at the centre of the establishment of the Kaaba, the primordial sanctuary in Mecca.

1.1 Building the Kaaba

The Qur’an explicitly describes Abraham and Ishmael raising the foundations of the Kaaba:

“And when Abraham raised the foundations of the House, and [with him] Ishmael, [saying], ‘Our Lord, accept this from us…’” (Qur’an 2:127)

This verse identifies them not only as worshippers but as architects of the House of God.

1.2 Dedication and Purification of the Sacred Space

Abraham and Ishmael are commanded to cleanse the House for those who perform worship, circumambulation, and devotion (Qur’an 2:125). Another passage speaks of Abraham leaving Ishmael’s descendants in the valley near the House to establish true worship (Qur’an 14:37), reinforcing their custodial role.

1.3 Universality of the Kaaba

The Qur’an describes the Kaaba as “the first House established for mankind” (Qur’an 3:96), giving it a universal, primordial character. Abraham and Ishmael thus appear not merely as historical figures but as founders of a sacred centre for all humanity.

In Islamic tradition, Abraham and Ishmael are understood as active constructors, purifiers, and guardians of the Kaaba — the earliest sanctuary dedicated to monotheistic worship.

⸻

♦️ 2. The Bible: Abraham, Isaac, and the Temple Mount

While the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh/Old Testament) also portrays Abraham as central to God’s covenantal plan, it does not attribute to him or to Isaac the establishment of a physical sanctuary.

2.1 Abraham and Isaac at Mount Moriah

Genesis 22 recounts the “Akedah,” or Binding of Isaac. God commands Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice “on one of the mountains in the land of Moriah” (Genesis 22:2).

Centuries later, 2 Chronicles 3:1 identifies this same region as the site of Solomon’s Temple:

“Then Solomon began to build the house of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord had appeared to David his father…”

This connection retroactively links the Akedah to the future Temple Mount. Yet the link is narrative and theological rather than architectural; Abraham and Isaac do not participate in constructing the sanctuary.

2.2 David and Solomon as Temple Builders

In the biblical tradition, the idea of a permanent sanctuary arises not with Abraham or Isaac but with King David. The Temple itself is built by Solomon (1 Kings 6), fulfilling David’s aspiration as narrated in 2 Samuel 7. Thus, temple-building is royal, not patriarchal.

⸻

♦️ 3. Key Difference: Builder vs. Symbol

A clear contrast emerges between the two scriptural traditions:

3.1 Qur’anic Perspective

• Abraham and Ishmael are direct builders and consecrators of the Kaaba.

• The sanctuary originates in their hands and through their supplication.

• The Kaaba becomes the focal point of monotheistic worship for all humanity.

3.2 Biblical Perspective

• Abraham and Isaac are linked to the site of the future Temple (Mount Moriah), but only symbolically.

• They do not build or establish a sanctuary.

• Temple-building is attributed to the Davidic-Solomonic monarchy.

3.3 Associative vs. Foundational

• The Bible connects Abraham and Isaac to the Temple through memory and location: the Akedah becomes part of Jerusalem’s sacred geography.

• The Qur’an connects Abraham and Ishmael to the Kaaba through construction and divine command: they physically establish the House of God.

⸻

♦️ Conclusion

Both the Bible and the Qur’an situate Abraham at the heart of sacred history, yet they portray his relationship to holy places in distinct ways. In the Qur’an, Abraham and Ishmael lay the physical and spiritual foundations of the Kaaba, making them architects of a universal sanctuary.

In the Bible, Abraham and Isaac are remembered for their obedience at Moriah, a site later reinterpreted as the location of the Temple, but they do not build it.

These contrasting narratives shape how each tradition understands sacred space, lineage, and the enduring legacy of Abraham and his sons.

Islamic Views on the Abrahamic and Sinai Covenants in Relation to Heritage and Relics

There is no specific Abrahamic relic that has been preserved through Jewish generations, similar to the Kaaba, the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad) and the Station of Abraham (Maqam Ibrahim) in Islam. The sole significant artifact associated with Jewish heritage is the Ark of the Covenant.

However, it is important to note that the Ark can be traced back to Moses rather than Abraham and was lost during the destruction of the First Temple. Consequently, Islamic scholars maintain that the Israelites were bound by the Sinai Covenant, while Muslims are considered to be under the Abrahamic Covenant. How does their argument go?

The argument presented by Islamic scholars regarding the Abrahamic Covenant and the Sinai Covenant is based on several theological and historical points. To understand their perspective, let’s break down the key elements:

- Abrahamic Covenant vs. Sinai Covenant: The Abrahamic Covenant is believed to be the original covenant between God and Abraham, which includes promises of land, descendants, and blessings.

The Sinai Covenant, also known as the Mosaic Covenant, was established between God and the Israelites through Moses at Mount Sinai. - Islamic view on continuity: Islamic scholars argue that Muslims are the true inheritors of the Abrahamic Covenant, which they consider to be universal and eternal.

They contend that the Sinai Covenant was specific to the Israelites and was temporary or conditional. - Lack of physical relics: The absence of a specific Abrahamic relic in Jewish tradition, comparable to the Kaaba, the Black Stone, or the Station of Abraham in Islam, is seen by some Islamic scholars as significant.

They argue that this absence might indicate a break in the direct line of Abrahamic heritage. - The Ark of the Covenant: While the Ark of the Covenant is a significant artifact in Jewish history, it is associated with Moses rather than Abraham.

Its loss during the destruction of the First Temple is sometimes interpreted by Islamic scholars as a symbolic end to the Sinai Covenant. - Islamic claim to Abrahamic heritage: Islamic scholars often emphasize the direct lineage of Muhammad to Abraham through Ishmael.

They argue that Islam represents a restoration of the original Abrahamic monotheism, unencumbered by later additions or alterations. - Universality vs. particularity: The Islamic view often presents the Abrahamic Covenant as universal, meant for all of humanity.

In contrast, they view the Sinai Covenant as particular to the Israelites and not binding on all people. - Supersessionism: Some Islamic interpretations incorporate a form of supersessionism, suggesting that Islam supersedes earlier revelations and covenants.

It’s important to note that this argument represents a specific Islamic perspective and is not universally accepted outside of Islamic scholarship. Jewish and Christian traditions have their own interpretations of these covenants and their ongoing relevance. The topic of covenants and their applicability is a complex theological issue with various interpretations across different faith traditions.

Does the Expansion of Islam in the Middle East Fulfill the Prophecy in Genesis?

⸻

📖 1. The Promise in Genesis

In the Book of Genesis (ch. 12, 15, 17), God promises Abraham that his descendants will inherit a specific land — described as stretching from the “River of Egypt” to the “Euphrates.”

• Abraham has two key lines of descendants:

• Isaac → leading to Jacob/Israel → the Israelites (the covenantal line).

• Ishmael → also blessed by God (Genesis 17:20), though not tied to the covenantal land promise.

✡️ In Jewish and Christian traditions, the covenantal promise of the land is linked specifically to Isaac’s descendants.

⸻

🌴 2. The Ishmaelite Connection and Later Arabs

• Islamic tradition traces Arab descent (and much of the Muslim world) through Ishmael, Abraham’s first son.

• Genesis records that Ishmael too will become a “great nation” (Genesis 21:18).

• Thus:

• Isaac’s line = covenantal inheritance.

• Ishmael’s line = blessing and greatness in its own right.

⸻

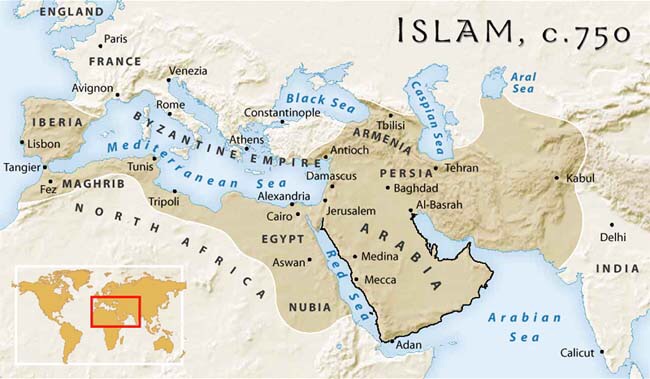

🌍 3. The Expansion of Islam

• In the 7th century, Islam arose in Arabia and rapidly spread across the Middle East and beyond.

• These lands overlap significantly with the territories mentioned in Genesis.

☪️ From an Islamic perspective: This spread reflects God’s promise to bless Ishmael’s descendants and make them into great nations across Abraham’s homeland.

✡️✝️ From Jewish and Christian perspectives: The covenantal inheritance remains with Israel, not Ishmael’s descendants.

⸻

🕊️ 4. Theological Interpretations

• ✡️ Jewish perspective: The covenant and land promise are eternal for Israel alone. Islam’s rise is historical but not covenantal fulfillment.

• ✝️ Christian perspective: Views differ — some see the promise fulfilled spiritually in Christ (extended to all believers), while others expect a future literal fulfillment for Israel.

• ☪️ Islamic perspective: Muslims see themselves as the true heirs of Abraham’s faith through Ishmael and Muhammad. The expansion of Islam is seen as a realization of God’s promise of greatness.

⸻

✅ Summary:

• ✡️/✝️ Jewish/Christian tradition: The specific land promise refers to Isaac’s descendants, not Ishmael’s.

• ☪️ Islamic tradition: The rapid growth and dominance of Ishmael’s descendants across Abraham’s homeland can be understood as a manifestation of God’s promise to Ishmael.