Azahari Hassim

Surah 10, verse 92, reads:

“Today We will preserve your body (O Pharaoh), so that you become a sign for those after you. But most people are heedless of Our signs.”

Some scholars contend that the discovery of Ramses’ body in modern times is viewed as a miraculous event in the Quran, specifically in Surah 10, verse 92. It resembles Moses’ parting of the Red Sea. As a result, they argue that Muhammad is the prophet mentioned in Deuteronomy 18, verse 18, similar to Moses. How do they express their argument?

The scholars who make this argument typically point to several key points to support their claim:

1. Discovery of Ramses’ body: They argue that the discovery of Pharaoh Ramses II’s body in modern times is a significant event that aligns with the story of Pharaoh’s body being preserved as a sign in Surah 10, verse 92 of the Quran. This miraculous preservation of Pharaoh’s body is seen as a fulfillment of that prophecy.

2. Resemblance to Moses’ parting of the Red Sea: The scholars suggest that the discovery of Ramses’ body can be seen as a parallel to the miracle of Moses parting the Red Sea, as both events involve extraordinary occurrences related to Pharaoh and Moses. This parallel further strengthens the connection between the two stories.

3. Muhammad as the prophet like Moses: In Deuteronomy 18, verse 18, the Bible mentions the coming of a prophet like Moses, whom God will raise up among the brethren of Israelites. Some scholars argue that Muhammad fits the description of this prophet due to similarities in their roles, teachings, and experiences with prophethood.

By combining these points, scholars argue that the discovery of Ramses’ body, the resemblance to Moses’ story, and the identification of Muhammad as the prophet like Moses provide evidence for the divine inspiration of the Quran and Muhammad’s status as a prophet in the line of Moses.

Muhammad, Torah and Hebrew prophets

Does Hagar’s prophecy in Genesis 21, verse 18, predate the Torah given to Moses?

Yes, Hagar’s prophecy in Genesis 21, verse 18, predates the Torah as given to Moses. The Book of Genesis, which includes the story of Hagar, is considered part of the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible) and traditionally attributed to Moses.

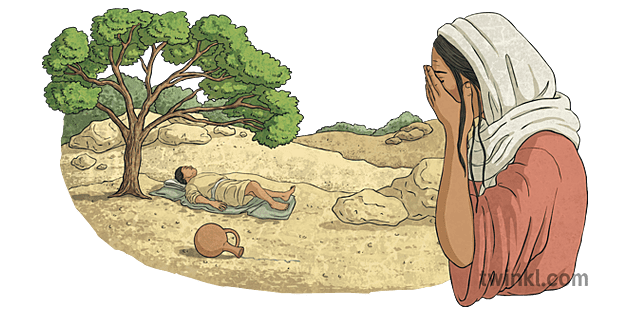

However, the events described in Genesis, including Hagar’s encounter with God and the prophecy concerning her son Ishmael, are believed to have occurred long before the time of Moses, around the patriarchal period.

The narrative in Genesis 21 describes Hagar and Ishmael in the context of Abraham’s family and is thus seen as part of the pre-Mosaic tradition. The Torah, or Pentateuch, as a compilation and codification, is generally understood to have been formalized during the time of Moses, which occurs much later in the biblical timeline.

Therefore, the events and prophecies in Genesis can be considered as part of the earlier history before the giving of the law to Moses.

What is the argument put forth by those who support the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, in contrast to Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah? Consequently, Muhammad, in contrast to Hebrew prophets such as Jesus, is not bound by the laws of the Torah.

Supporters of the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, argue that this connection sets Muhammad apart from Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah. Here is a detailed explanation of their argument:

1. Pre-Torah Origins of Hagar’s Prophecy

Proponents argue that Hagar’s prophecy, as mentioned in Genesis 21, verse 18, predates the Torah given to Moses. This prophecy concerns Hagar’s son, Ishmael, who is promised to become a great nation. This predates the formalization of the Torah, which is traditionally attributed to Moses and his time.

2. Reiteration and Fulfillment in Islamic Rituals

The Torah reiterates Hagar’s prophecy, but its fulfillment is seen in Islamic practices, particularly the Hajj pilgrimage. The Hajj, which involves rituals connected to Hagar and Ishmael, is viewed as a direct link to their legacy. This pilgrimage is a central practice in Islam, signifying the prophecy’s fulfillment and its importance in Islamic tradition.

3. Marginalization by Ancient Israelite Scribes

It is suggested that ancient Israelite scribes attempted to downplay the significance of Hagar and Ishmael due to theological and political reasons. This marginalization aimed to elevate the prominence of Isaac and the Israelite lineage over Ishmael. The argument posits that the biblical narrative was shaped in a way that selectively emphasized aspects favorable to the Israelite lineage.

Contrast with Hebrew Prophets

1. Association with the Torah

Hebrew prophets are closely linked to the Torah, which is seen as the foundation of their prophetic authority. The Torah, given to Moses, contains the laws and ethical teachings that Hebrew prophets were tasked with interpreting and enforcing. This connection establishes a continuous line of prophetic tradition rooted in the Mosaic covenant.

2. Muhammad’s Independent Prophetic Lineage

In contrast, Muhammad’s prophethood is associated with the Abrahamic covenant through Ishmael, rather than the Mosaic covenant. This distinction is significant in Islamic theology, which views Muhammad’s message as a continuation and fulfillment of the Abrahamic faith, independent of the Mosaic laws. This perspective underscores the universality of Muhammad’s revelation, intended for all humanity, rather than being confined to the specific legal and ritual practices of the Jewish people.

Theological Implications

1. Universal Prophetic Tradition

By associating Muhammad with a prophecy that predates the Torah, supporters argue that prophetic messages have been universal and ongoing throughout human history. This places Islam within a broader, inclusive prophetic tradition that transcends Jewish ethnic and religious boundaries. It emphasizes the continuity of divine guidance from the time of Abraham through to Muhammad.

2. Distinct Covenants

The argument also highlights the existence of distinct covenants in the Abrahamic religions. While the Hebrew prophets operate under the covenant of Moses and the Sinai revelation, Muhammad is seen as part of the covenant given to Abraham and Ishmael. This theological distinction reinforces the idea that different prophetic traditions are validated by separate covenants within the broader framework of Abrahamic faiths.

In summary, the argument linking Muhammad’s prophethood to Hagar’s prophecy emphasizes its pre-Torah origins, fulfillment in Islamic Hajj, and the marginalization of Hagar’s significance by ancient Israelite scribes. This perspective contrasts Muhammad’s universal and independent prophetic lineage with the Hebrew prophets’ association with the Torah, highlighting distinct covenants and a broader prophetic tradition.

Examining Claims of Scribal Interpolation: Who Was Abraham’s Sacrificial Son, Ishmael or Isaac?

Was there a scribal interpolation in the Torah regarding which son, Ishmael or Isaac, Abraham was commanded to sacrifice, as suggested by the celebration of Eid al-Adha (Feast of Sacrifice) in Islam?

Some Islamic scholars argue that Eid al-Adha (Feast of Sacrifice) points to a scribal interpolation in the Torah regarding which son Abraham was commanded to sacrifice. Their argument for scribal interpolation is articulated as follows:

Islamic tradition holds that it was Ishmael, not Isaac, whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice. This belief forms the basis for the celebration of Eid al-Adha (Feast of Sacrifice), one of the most important festivals in Islam.

Scholars who support this view present several arguments:

1. Primacy of Ishmael: They argue that Ishmael, being Abraham’s firstborn son, was the original heir to the covenant and thus the logical choice for such a significant test of faith.

2. Quranic Account: The Quran’s narrative of the sacrifice does not explicitly name the son, but contextual evidence and Islamic tradition point to Ishmael. This interpretation stems from the chronological events presented in the Quran, indicating that the promise of Isaac’s birth occurred after the narrative of the sacrifice, thereby suggesting that Ishmael was the son mentioned in that context.

3. Historical Context: These scholars suggest that ancient Israelite scribes may have altered the original text to emphasize Isaac’s role, shifting the focus away from Ishmael to establish a stronger theological foundation for Israelite claims.

4. Geographical Inconsistencies: They point out that the biblical account mentions Mount Moriah, while Islamic tradition places the event near Mecca, where Ishmael and Hagar settled.

5. Linguistic Analysis: Some argue that careful examination of the original Hebrew text reveals inconsistencies that suggest later editing.

If this interpretation is accepted, it would have significant implications:

It would challenge the traditional Jewish and Christian understanding of the Abrahamic covenant.

It would support the Islamic view of Ishmael as a key figure in the Abrahamic covenant and narrative.

It would reinforce the Islamic belief in the Quran as a correction to earlier scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospel.