Azahari Hassim

According to established tradition, prior to the advent of Muhammad, the Arabs believed that their ancestor Abraham was on the verge of offering his son Ishmael as a sacrifice to God. It is believed that their pre-Islamic tradition about Ishmael predates the Torah given to Moses. How is their argument articulated?

Scholars argue that the oral traditions of the Arabs, including those surrounding Ishmael, predate the written texts of the Torah. This assertion is based on the notion that oral traditions can be older than their written counterparts, as they may have been passed down through generations long before being codified in scripture.

The argument that the pre-Islamic Arab tradition about Ishmael predates the Torah given to Moses is articulated through several points:

1. Historical Narratives: Early Arab traditions held that Ishmael, not Isaac, was the son Abraham was commanded to sacrifice. This belief is deeply rooted in the cultural and religious narratives of pre-Islamic Arabia.

2. Religious Significance: The story of Ishmael’s near-sacrifice is significant in Islam, where it is believed that both Abraham and Ishmael willingly submitted to God’s command. This act of submission is seen as a profound demonstration of faith and obedience.

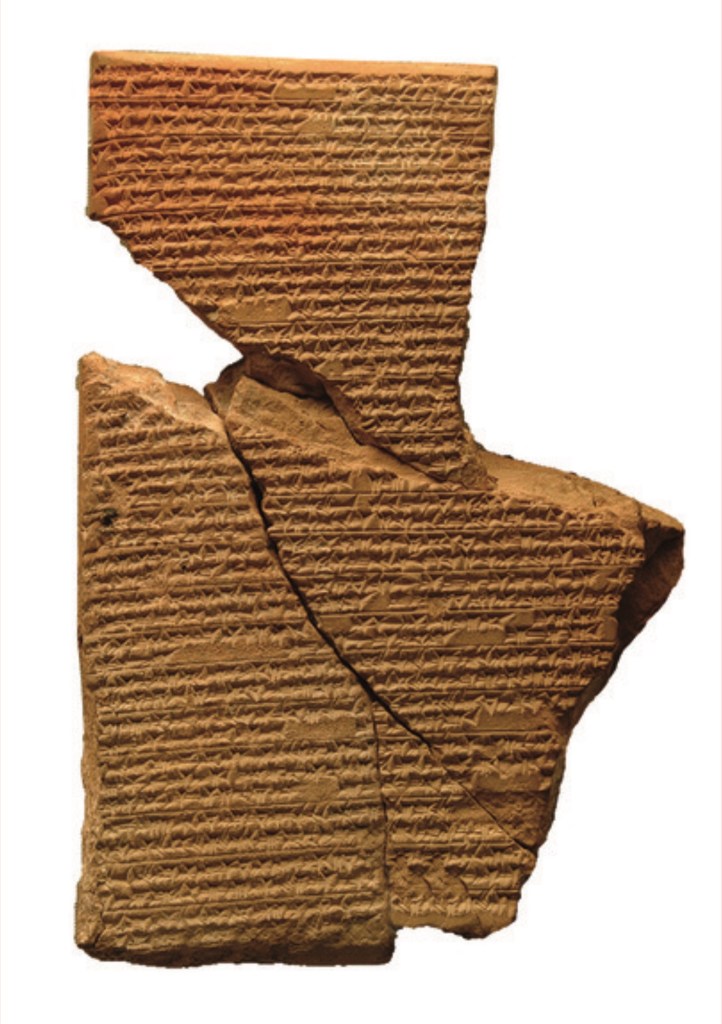

3. Cultural Artifacts: Some early Muslim scholars argued that the horns of the ram, which was sacrificed in place of Ishmael, were once displayed in the Kaaba, suggesting a long-standing tradition that predates Islamic scripture.

4. Jealousy Argument: There is also an argument that Jews claimed Isaac was the intended sacrifice out of jealousy, as Ishmael is considered the ancestor of the Arabs.

These points collectively support the belief that the tradition of Ishmael’s near-sacrifice has ancient roots, predating the Torah and reflecting the unique relationship between God and the Arab people.

Interestingly, before the rise of Islam, ancient Arabs in Mecca circumcised their children at the age of 13 or 14. Did they inherit this practice from the Torah, which requires circumcision at eight days, or was it a tradition tracing back to Abraham that predated the Torah?

It is plausible that the tradition of circumcision among ancient Arabs in Mecca traced back to Abraham, who is considered a common ancestor by both Jews and Arabs. It could be that this practice was passed down through generations independently of any direct influence from the Torah or Judaism.

Hagar’s Prophecy predated the Torah

It is believed that the prophecy of Hagar predated the Torah revealed to the Israelites. The Torah reiterated her prophecy, whose fulfillment is realized in the ritual Hajj of Islam. Some argue that the scribes of ancient Israelites attempted to tone down its importance. How is the argument articulated?

The argument as presented suggests that the prophecy of Hagar, which is believed to have predated the Torah, finds its fulfillment in the Islamic ritual of Hajj, and that the scribes of ancient Israel attempted to diminish its significance. Here’s how this argument is explained:

1. Pre-Torah origins: This argument posits that the prophecy of Hagar and her descendants, including Ishmael, existed prior to the revelation of the Torah to Moses. Supporters of this view often point to the genealogical and historical connections between Hagar and Ishmael and the founding of the Arab people.

2. Prophecy reiterated in Torah: The claim is made that the Torah, when it was revealed to the Israelites, reiterated and acknowledged the prophecy related to Hagar and Ishmael. This acknowledgment can be found in the biblical narrative where Hagar and Ishmael’s story is mentioned.

3. Importance of the Hajj ritual: Proponents then assert that the fulfillment of Hagar’s prophecy, as reiterated in the Torah, can be seen in the Islamic ritual of Hajj. They argue that Hajj, which is a pilgrimage to the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, is seen as a direct link to Hagar and Ishmael and represents the fulfillment of their destiny. This ritual is regarded as a significant practice in Islam and is central to the religious identity of Muslims.

4. Suppression of Hagar’s significance: The argument continues by suggesting that the scribes of ancient Israel attempted to downplay the importance of Hagar and her descendants, including Ishmael, due to theological and political motivations. It is proposed that, in shaping the biblical narrative, these scribes might have marginalized or selectively emphasized certain aspects to elevate the prominence of Isaac and the Israelite lineage over Ishmael.

It’s important to note that this argument reflects a particular perspective and interpretation. There are different viewpoints on this topic, and scholars hold a wide array of opinions regarding the relationship between biblical narratives, biblical redaction, and the Islamic tradition.

Muhammad and the Hebrew prophets

What is the argument put forth by those who support the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, in contrast to Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah? Consequently, Muhammad, in contrast to Hebrew prophets such as Jesus, is not bound by the laws of the Torah.

Supporters of the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, argue that this connection sets Muhammad apart from Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah. Here is a detailed explanation of their argument:

1. Pre-Torah Origins of Hagar’s Prophecy

Proponents argue that Hagar’s prophecy, as mentioned in Genesis 21, verse 18, predates the Torah given to Moses. This prophecy concerns Hagar’s son, Ishmael, who is promised to become a great nation. This predates the formalization of the Torah, which is traditionally attributed to Moses and his time.

2. Reiteration and Fulfillment in Islamic Rituals

The Torah reiterates Hagar’s prophecy, but its fulfillment is seen in Islamic practices, particularly the Hajj pilgrimage. The Hajj, which involves rituals connected to Hagar and Ishmael, is viewed as a direct link to their legacy. This pilgrimage is a central practice in Islam, signifying the prophecy’s fulfillment and its importance in Islamic tradition.

3. Marginalization by Ancient Israelite Scribes

It is suggested that ancient Israelite scribes attempted to downplay the significance of Hagar and Ishmael due to theological and political reasons. This marginalization aimed to elevate the prominence of Isaac and the Israelite lineage over Ishmael. The argument posits that the biblical narrative was shaped in a way that selectively emphasized aspects favorable to the Israelite lineage.

Contrast with Hebrew Prophets

1. Association with the Torah

Hebrew prophets are closely linked to the Torah, which is seen as the foundation of their prophetic authority. The Torah, given to Moses, contains the laws and ethical teachings that Hebrew prophets were tasked with interpreting and enforcing. This connection establishes a continuous line of prophetic tradition rooted in the Mosaic covenant.

2. Muhammad’s Independent Prophetic Lineage

In contrast, Muhammad’s prophethood is associated with the Abrahamic covenant through Ishmael, rather than the Mosaic covenant. This distinction is significant in Islamic theology, which views Muhammad’s message as a continuation and fulfillment of the Abrahamic faith, independent of the Mosaic laws. This perspective underscores the universality of Muhammad’s revelation, intended for all humanity, rather than being confined to the specific legal and ritual practices of the Jewish people.

Theological Implications

Universal Prophetic Tradition

By associating Muhammad with a prophecy that predates the Torah, supporters argue that prophetic messages have been universal and ongoing throughout human history. This places Islam within a broader, inclusive prophetic tradition that transcends Jewish ethnic and religious boundaries. It emphasizes the continuity of divine guidance from the time of Abraham through to Muhammad.

Distinct Covenants

The argument also highlights the existence of distinct covenants in the Abrahamic religions. While the Hebrew prophets operate under the covenant of Moses and the Sinai revelation, Muhammad is seen as part of the covenant given to Abraham and Ishmael. This theological distinction reinforces the idea that different prophetic traditions are validated by separate covenants within the broader framework of Abrahamic faiths.

In summary, the argument linking Muhammad’s prophethood to Hagar’s prophecy emphasizes its pre-Torah origins, fulfillment in Islamic Hajj, and the marginalization of Hagar’s significance by ancient Israelite scribes. This perspective contrasts Muhammad’s universal and independent prophetic lineage with the Hebrew prophets’ association with the Torah, highlighting distinct covenants and a broader prophetic tradition.

The Prophecy of Hagar and Its Fulfillment: A Comparative Analysis of Genesis 21:18 and Isaiah 60:7

There is a belief that the prophecy of Hagar in Genesis 21, verse 18, holds more weight than Isaiah 60, verse 7, which is linked to and completes the former. How is this understanding conveyed?

The belief that the prophecy of Hagar in Genesis 21, verse 18, holds more weight than Isaiah 60, verse 7, which is linked to and completes the former, can be understood through a close examination of the biblical texts and their contexts. Here’s how this understanding is conveyed:

1. Genesis 21, verse 18 (The Prophecy of Hagar).

This verse is part of the story where God speaks to Hagar after she and her son, Ishmael, are sent away by Abraham. Hagar is distraught, fearing for her son’s life in the desert.

The verse reads: Arise, lift up the lad, and hold him in thine hand; for I will make him a great nation.”

This prophecy directly promises that Ishmael will become a great nation. This is a foundational promise, as it assures Hagar of her son’s future and his importance in God’s plan.

2. Isaiah 60, verse 7 (Completion of the Prophecy).

This chapter of Isaiah deals with the future glory of Zion, depicting a time of great prosperity and the gathering of nations to honor God.

The verse reads: “All the flocks of Kedar shall be gathered together unto thee, the rams of Nebaioth shall minister unto thee: they shall come up with acceptance on mine altar, and I will glorify the house of my glory.”

Both Kedar and Nebaioth are descendants of Ishmael. This verse indicates the fulfillment and continuation of the promise given to Hagar, showing that Ishmael’s descendants will play a significant role in the future worship and honor of God.

3. Interconnection and Weight:

The prophecy in Genesis 21, verse 18, is seen as having “more weight” because it is the initial divine promise regarding Ishmael, establishing his importance and future. It is a direct communication from God to Hagar at a crucial moment. Isaiah 60, verse 7, is viewed as the completion or continuation of this promise. It confirms and elaborates on the fulfillment of God’s plan for Ishmael’s descendants, showing their eventual integration into the worship of God and their contribution to the glory of Zion.

The “weight” of Genesis 21, verse 18, lies in its foundational nature, while Isaiah 60, verse 7, provides a more detailed and expanded vision of the fulfillment of that initial promise.

This understanding is conveyed by recognizing that the original promise to Hagar is the cornerstone of the prophecy concerning Ishmael and his descendants.

The later prophetic vision in Isaiah builds upon this foundation, demonstrating the fulfillment of God’s promise in a broader and more comprehensive way. Therefore, while Isaiah 60, verse 7 is significant in its completion of the prophecy, Genesis 21, verse 18, holds a primary and foundational weight in the narrative.

Some believe that Isaiah 60, verse 7, is related to the Hajj ritual, and is the fulfillment of Hagar’s prophecy regarding Ishmael in Genesis 21, verse 18. How is this interpretation presented?

This is an interesting question. The interpretation that Isaiah 60, verse 7, is related to the Hajj ritual and the fulfillment of Hagar’s prophecy regarding Ishmael is based on the following assumptions:

The verse reads:

“All the flocks of Kedar will be gathered to you, The rams of Nebaioth will serve you; They will go up on My altar with acceptance, And I will glorify My glorious house.”

The flocks of Kedar and the rams of Nebaioth in Isaiah 60, verse 7, refer to the descendants of Ishmael, who was the son of Abraham and Hagar, and the ancestor of the Arabs. Kedar and Nebaioth were two of Ishmael’s sons (Genesis 25, verse 13).

The altar and the glorious house mentioned in Isaiah 60, verse 7, refer to the Kaaba. The Kaaba is a sacred building in Mecca that has a cube shape. Muslims believe it was constructed by Abraham and Ishmael. It serves as the direction of prayer and is also the destination for the Hajj pilgrimage.

The acceptance of the offerings on the altar and the glorification of the house in Isaiah 60, verse 7, refer to Muslims performing their Hajj, known as the Feast of Sacrifice. This sacrifice is performed in remembrance of Prophet Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Ishmael and as a demonstration of submission to Allah’s will.

Furthermore, it is a prophecy of God’s acceptance and blessing of the Ishmaelites, who worship Him at the Kaaba in sincerity and submission, as He promised Hagar in Genesis 21, verse 18, “I will make him into a great nation.”

This interpretation is presented by some Muslim scholars and commentators, who see it as a proof of the truth and validity of Islam and the Hajj ritual.