Azahari Hassim

Do Ishmaelites possess a distinct tradition that traces back to their forefather, apart from the biblical narrative?

The Ishmaelites, as referred to in various historical and religious texts, are traditionally considered to be the descendants of Ishmael, the first son of Abraham and Hagar. Ishmael is an important figure in Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions, but the traditions and histories diverge in significant ways across these faiths, particularly in Islam.

In Biblical Narrative:

In the Bible, particularly the Book of Genesis, Ishmael is portrayed as the elder half-brother of Isaac. The narrative describes how he and his mother Hagar were sent away into the desert by Abraham at the behest of Sarah (Isaac’s mother).

The biblical narrative primarily depicts Ishmael as the progenitor of the Ishmaelites, often considered ancestors of the Arab peoples. However, detailed traditions specifically tracing back to Ishmael in terms of rituals, laws, or unique religious practices distinct from later Jewish or Christian traditions are not extensively documented within the Bible itself.

In Islamic Tradition:

In Islamic tradition, however, Ishmael (Ismail in Arabic) holds a significantly different and more detailed historical and spiritual legacy. Islam regards Ishmael as a prophet and an ancestor of Muhammad, which is distinct from the biblical account in several key aspects:

Foundation of Mecca:

Islamic traditions hold that Ishmael and his father Abraham were involved in the rebuilding of the Kaaba in Mecca, which is the holiest site in Islam.

The Hajj Ritual:

Many rituals performed during the Hajj (the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca) are commemorated in the context of events involving Ishmael and Abraham. For instance, the ritual of the Sa’i, walking between the hills of Safa and Marwah, is a re-enactment of Hagar’s search for water for her baby son Ishmael.

Sacrifice:

The Islamic festival of Eid al-Adha commemorates the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son in obedience to God’s command, which in Islamic tradition is believed to have been Ishmael, rather than Isaac as in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Cultural and Historical Perspective:

Beyond religious texts, the identity and historical interpretations of the Ishmaelites have evolved in various cultures. In some traditions, the Ishmaelites are often conflated with Arab tribes, and thus Ishmael is considered an important forefather of Arabs. This lineage has sometimes been used historically to claim a shared ancestry for Arab peoples.

Conclusion:

While the biblical narrative does not extensively detail distinct traditions that trace back specifically to Ishmael separate from broader Jewish and Christian practices, Islamic tradition provides a rich, detailed cultural and religious heritage tracing back to Ishmael.

This includes specific rituals and celebrations that are integral to Islamic practice today. These distinctions highlight the varying ways in which the figure of Ishmael has been revered and remembered across different cultures and religions.

Martin Luther (1483–1546):

“The Turk [Muslim] is the rod of the wrath of the Lord our God… If we were such Christians as we ought to be, the Turk would not have grown so powerful, but he would have stayed in his own land.”

Midrashic and Islamic Interpretations of Abraham’s Sacrifice: The Identity of the ‘Only Son’

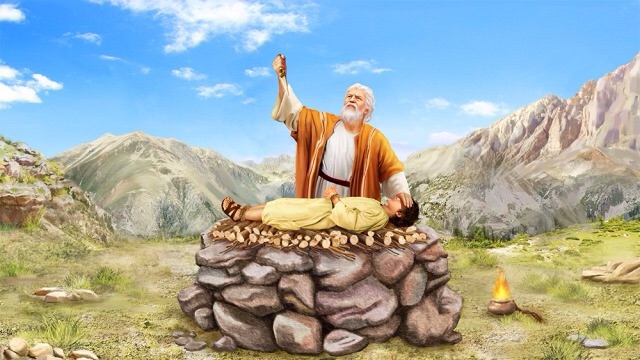

What is the explanation of the Midrash about Isaac being called “thy only son” when God ordered Abraham to sacrifice his son? In Islamic tradition, it is Ishmael and not Isaac, whom God instructed Abraham to sacrifice his son.

The Midrash, which is a form of rabbinic literature that provides interpretative commentary on the Torah, offers several explanations for why Isaac is referred to as Abraham’s “only son” in the context of the Akedah (the Binding of Isaac). Here are some key points from the Midrashic perspective:

The Midrash explains that while Abraham had two sons, Isaac held a unique status as the son of the covenant. He was born to Sarah, Abraham’s wife, and was seen as the fulfillment of God’s promise. Isaac is considered the spiritual heir of Abraham, chosen to carry on the legacy of monotheism and the covenant with God.

In some Midrashic accounts, when God says “your only son,” Abraham responds by saying he has two sons. God then specifies “the one whom you love,” and Abraham says he loves both. Finally, God says “Isaac,” clarifying His command. The phrase “only son” is interpreted to mean the son who is singularly devoted to God, emphasizing Isaac’s spiritual qualities rather than his birth order.

Some rabbinical commentators suggest that the Hebrew word for “only” (יחיד) can also mean “unique” or “special,” rather than strictly “sole.” The use of “only son” is seen as part of the test, emphasizing the magnitude of what God is asking Abraham to sacrifice.

In contrast, the Islamic tradition, as recorded in the Quran, identifies Ishmael as the son whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice. The Quranic narrative does not explicitly name the son, but Islamic tradition and many Muslim scholars have historically identified him as Ishmael. This is partly based on the sequence of events in the Quran, which suggests that the promise of Isaac’s birth came after the sacrifice narrative, implying Ishmael was the son involved.

The differences between the Jewish and Islamic narratives have been the subject of theological discussions and interpretations. Some scholars suggest that each tradition emphasizes different aspects of the story to highlight their theological and historical narratives.

While the Islamic tradition interprets the sacrificial son to be Ishmael based on him being the firstborn, Judaism relies on the Torah’s explicit identification of Isaac and his special covenantal status to explain why Isaac is called the “only son” in this context. The two traditions remain at odds on this important narrative.

In summary, the explanation of the Midrash about Isaac being called “thy only son” is a matter of religious interpretation, with Jewish and Islamic traditions holding different views on who was the son intended for sacrifice.

A HISTORY OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH

by Lars P. Qualben

Islam and the Greek Church

While Christianity was gaining mastery over the barbarian tribes of western Europe, a new Theocracy arising in Arabia expanded to tremendous proportions. It was modeled on that of Moses. Mohammed (570-632) was its founder, its prophet, and its military leader. Sprung from the distinguished tribe of the Koreish, the custodians of the sacred shrine of the Kaaba (cube), he was born in the holy city of Mecca.

Within this temple was preserved the sacred black stone which the Mohammedans say was originally white as milk, but turned black because of the sin of man. Mohammed was brought up by his relatives without any education. First a shepherd, he later became a merchant and a camel driver.

The religion of his people was heathenism, but Mohammed and his tribe came in frequent contact with Judaism and degenerate forms of Christianity (Ebionism, Arianism, and Sabellianism). A commercial journey through Syria with an uncle brought Christianity and Judaism to his special attention.

In 610, at the age of forty, Mohammed appeared as a prophet, proclaiming a new religion sometimes called Islam, meaning “submission to Allah,” sometimes Mohammedanism after its. The religious system of Islam may be summed up as follows: God, or Allah, is one. He is omnipotent and omniscient. Submission to Him is the central principle in the system.

Hence the name Islam. All events are foreordained, and men must submit to this unchangeable order of things without a murmur. There are two classes of angels: good and bad. Allah has given His revelation in the Scriptures, that is, in the Quran and in the Sunna, a great body of traditions of Mohammed’s sayings.

God has sent prophets such as Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. But the greatest of them all is Mohammed, the Paraclete” promised by Jesus.