Azahari Hassim

It is believed that pre-Islamic Arab traditions concerning Hagar, sacrifice of Ishmael, and circumcision predate the Torah given to the children of Israel. How is this argument articulated?

The argument that pre-Islamic Arab traditions concerning Hagar, the sacrifice of Ishmael, and circumcision predate the Torah given to the children of Israel is often articulated by examining historical, religious, and cultural contexts. Here’s how this argument is typically laid out:

- Historical Context: Proponents of this argument suggest that the Arabian Peninsula had its own religious and cultural traditions long before the advent of Islam. These traditions were oral and transmitted through generations, which could predate the written texts of the Torah.

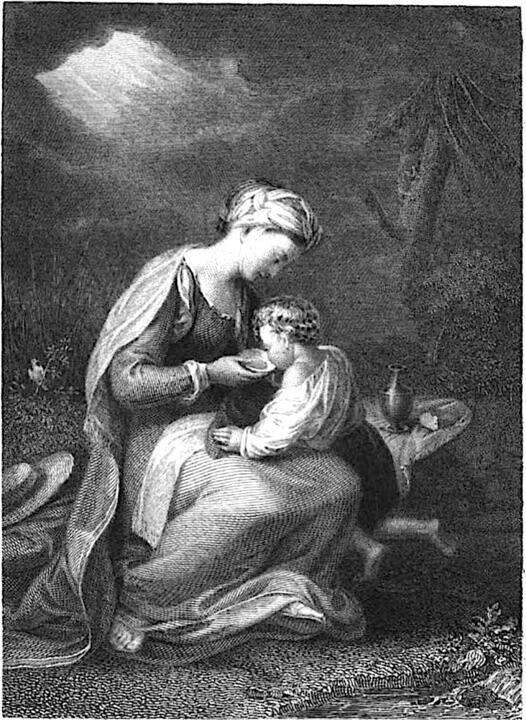

- Hagar and Ishmael: In the Islamic tradition, Hagar and Ishmael are considered important figures. Hagar, a maidservant of Sarah (Abraham’s wife), and her son Ishmael were sent away to the desert. This narrative is similar but not identical to the one found in the Torah. The significance of Hagar and Ishmael in Arab tradition suggests that their story was well-established among Arabs before the advent of Islam and possibly before the Torah was written.

- Sacrifice of Ishmael: Islamic tradition holds that Abraham was commanded to sacrifice his son Ishmael, not Isaac as in the Torah. This narrative is central to the Islamic festival of Eid al-Adha. The belief is that this tradition was already present among Arabs and was later formalized in Islamic texts. The argument is that since this tradition is integral to Arab culture and predates the Quran, it could also predate the Torah.

- Circumcision: Circumcision is a practice shared by both Jewish and Islamic traditions. In Islam, it is considered a practice that predates the Quran, suggesting it was already a well-established ritual among pre-Islamic Arabs. The continuity of this practice in Arab culture supports the argument that it was part of their tradition before the Torah was given.

- Cultural Transmission: The argument includes the idea that cultural and religious practices can be transmitted and preserved orally for generations. The Arabs, being a largely oral society, would have maintained their traditions independently of written texts. This oral transmission is posited to have preserved these traditions from a time predating the written Torah.

- Comparative Religious Studies: Scholars who support this view often compare religious texts and traditions. They argue that similarities between the Jewish and Arab narratives do not necessarily indicate borrowing from the Torah but rather point to a shared or parallel development of traditions.

In summary, the argument is that these traditions were part of the pre-Islamic Arab cultural and religious fabric, transmitted orally over generations, and thus could predate the written accounts of the Torah. This perspective emphasizes the antiquity and independence of Arab traditions in relation to Jewish scripture.

Muhammad and the Hebrew prophets

What is the argument put forth by those who support the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, in contrast to Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah? Consequently, Muhammad, in contrast to Hebrew prophets such as Jesus, is not bound by the laws of the Torah.

Supporters of the idea that the prophethood of Muhammad is linked to Hagar’s prophecy, which predates the Torah, argue that this connection sets Muhammad apart from Hebrew prophets who are associated with the Torah. Here is a detailed explanation of their argument:

1. Pre-Torah Origins of Hagar’s Prophecy:

Proponents argue that Hagar’s prophecy, as mentioned in Genesis 21, verse 18, predates the Torah given to Moses. This prophecy concerns Hagar’s son, Ishmael, who is promised to become a great nation. This predates the formalization of the Torah, which is traditionally attributed to Moses and his time.

2. Reiteration and Fulfillment in Islamic Rituals:

The Torah reiterates Hagar’s prophecy, but its fulfillment is seen in Islamic practices, particularly the Hajj pilgrimage. The Hajj, which involves rituals connected to Hagar and Ishmael, is viewed as a direct link to their legacy. This pilgrimage is a central practice in Islam, signifying the prophecy’s fulfillment and its importance in Islamic tradition.

3. Marginalization by Ancient Israelite Scribes:

It is suggested that ancient Israelite scribes attempted to downplay the significance of Hagar and Ishmael due to theological and political reasons. This marginalization aimed to elevate the prominence of Isaac and the Israelite lineage over Ishmael. The argument posits that the biblical narrative was shaped in a way that selectively emphasized aspects favorable to the Israelite lineage.

Contrast with Hebrew Prophets

1. Association with the Torah:

Hebrew prophets are closely linked to the Torah, which is seen as the foundation of their prophetic authority. The Torah, given to Moses, contains the laws and ethical teachings that Hebrew prophets were tasked with interpreting and enforcing. This connection establishes a continuous line of prophetic tradition rooted in the Mosaic covenant.

2. Muhammad’s Independent Prophetic Lineage:

In contrast, Muhammad’s prophethood is associated with the Abrahamic covenant through Ishmael, rather than the Mosaic covenant. This distinction is significant in Islamic theology, which views Muhammad’s message as a continuation and fulfillment of the Abrahamic faith, independent of the Mosaic laws. This perspective underscores the universality of Muhammad’s revelation, intended for all humanity, rather than being confined to the specific legal and ritual practices of the Jewish people.

Theological Implications

1. Universal Prophetic Tradition:

By associating Muhammad with a prophecy that predates the Torah, supporters argue that prophetic messages have been universal and ongoing throughout human history. This places Islam within a broader, inclusive prophetic tradition that transcends Jewish ethnic and religious boundaries. It emphasizes the continuity of divine guidance from the time of Abraham through to Muhammad.

2. Distinct Covenants:

The argument also highlights the existence of distinct covenants in the Abrahamic religions. While the Hebrew prophets operate under the covenant of Moses and the Sinai revelation, Muhammad is seen as part of the covenant given to Abraham and Ishmael. This theological distinction reinforces the idea that different prophetic traditions are validated by separate covenants within the broader framework of Abrahamic faiths.

In summary, the argument linking Muhammad’s prophethood to Hagar’s prophecy emphasizes its pre-Torah origins, fulfillment in Islamic Hajj, and the marginalization of Hagar’s significance by ancient Israelite scribes. This perspective contrasts Muhammad’s universal and independent prophetic lineage with the Hebrew prophets’ association with the Torah, highlighting distinct covenants and a broader prophetic tradition.

How did God fulfill the prophecy of Hagar, the mother of Ishmael, in the desert?

Some believe that the prophecy in the Torah (Genesis 21 verse 18) was fulfilled when God established Hajj as an Islamic rite. Pilgrims perform Sa’i in memory of Hagar, who searched for water for her infant son, Ishmael, in the desert, and God provided them with the well of Zamzam. Sa’i, which involves walking seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwa in Mecca, is one of the essential rituals of Hajj and Umrah. How is this argument articulated?

There is a belief among some Muslims that the prophecy mentioned in Genesis 21 verse 18 was fulfilled through the establishment of Hajj in Islam. This verse of the Torah prophesies that God will make a great nation from the descendants of Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar. The argument connecting the Islamic narrative with the story in the Torah can be articulated through a few key points:

1. Biblical Story of Hagar and Ishmael: In the Torah, the story of Hagar and her son Ishmael, who were cast into the desert, is recounted. In Genesis 21 verse 18, God tells Hagar,

“Lift up the boy and hold him fast with your hand, for I will make him into a great nation.”

This is often interpreted as a divine promise of Ishmael’s survival and future significance.

2. Link to the Prophecy: The argument connects the establishment of Hajj, including the ritual of Sa’i, to the fulfillment of the prophecy in Genesis. It’s posited that God’s establishment of these rituals and the continued commemoration by millions of Muslims is a fulfillment of the promise made to Hagar regarding Ishmael.

In summary, the act of Sa’i is not only a way for pilgrims to remember and honor Hagar’s struggle but also to symbolize the fulfillment of the prophecy in the Torah through the establishment of the ritual of Hajj in Islam.

lshmael

in the Old Testament, son of Abraham and his wife Sarah’s Egyptian maid Hagar; traditional ancestor of Muhammad and the Arab people. He and his mother were driven away by Sarah’s jealousy. Muslims believe that it was Ishmael, not Isaac, whom God commanded Abraham to sacrifice, and that Ishmael helped Abraham build the Ka’aba in Mecca.

Depictions of Hagar and Ishmael in Midrash Literature

How are Hagar and Ishmael depicted in the Midrash literature?

1. Hagar

Hagar is a complex and multifaceted character in Midrash literature. Several key themes and interpretations emerge from various Midrashic texts:

Royal Origin and Humility: According to the Midrash, Hagar was the daughter of Pharaoh, the king of Egypt. She chose to become a maidservant in Sarah’s house after witnessing the miracles performed by God for Sarah, indicating her humility and recognition of divine power.

Relationship with Sarah: The relationship between Hagar and Sarah is depicted as strained and contentious. Initially, Sarah persuades Abraham to take Hagar as a second wife in hopes of bearing children through her. However, once Hagar becomes pregnant, she looks down upon Sarah, leading to increased tension and mistreatment. This dynamic highlights the complexities and rivalries within the household.

Spirituality and Divine Encounters: Hagar is portrayed as a spiritually sensitive and righteous woman. She is one of the few individuals in the Bible to whom an angel of God appears directly. This encounter occurs when she flees into the wilderness, where the angel instructs her to return to Sarah and promises that her son, Ishmael, will be the progenitor of a great nation.

Reconciliation and Return: Some Midrashic traditions suggest that Hagar, identified as Keturah, returns to Abraham after Sarah’s death and remarries him. This reconciliation is facilitated by Isaac, who brings her back to his father, indicating a resolution of past conflicts and a continuation of her bond with Abraham.

2. Ishmael

Ishmael’s depiction in Midrash literature is equally nuanced, reflecting his complex role in Abraham’s family and his legacy:

Birth and Name: Ishmael’s name, meaning “God hears,” signifies the divine attention and promise given to Hagar regarding her son. The angel’s prophecy that Ishmael would be a “wild man” and live in conflict with others underscores his future as a formidable and independent figure.

Conflict with Isaac: The tension between Ishmael and Isaac is a recurring theme. Midrashic interpretations often highlight the rivalry and potential threats posed by Ishmael to Isaac, Sarah’s son. This conflict ultimately leads to Hagar and Ishmael’s expulsion from Abraham’s household.

Repentance and Legacy: Despite the initial conflicts, some Midrashic texts depict Ishmael as repenting and returning to the faith of his father, Abraham. This act of repentance and reconciliation is significant, as it portrays Ishmael in a more positive light, emphasizing his eventual alignment with Abraham’s spiritual legacy.

Descendants and Influence: Ishmael is considered the ancestor of several tribes and is linked to the Arab and Bedouin peoples. His descendants are seen as both a fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham and as a source of ongoing tension with the Israelites.

Conclusion

In Midrash literature, Hagar and Ishmael are depicted with a blend of complexity, spirituality, and conflict. Hagar’s humility, spiritual encounters, and eventual reconciliation with Abraham contrast with the initial strife she experiences with Sarah.

Ishmael’s journey from conflict to repentance highlights his significant yet contentious role in Abraham’s lineage. These narratives provide rich material for understanding the broader themes of faith, conflict, and reconciliation within the Abrahamic traditions.